When Rocks Became Clouds

It's cloud illusions I recall

I really don't know clouds at all

— “Both Sides Now”, song by Joni Mitchell

To name a thing is how we think we know it.

There has been much investigation on how language affects our thinking. One famous study gave us the Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis, which posits that our native tongue influences how we think about the world. In our minds and in our speech, we create our own narratives and according to this hypothesis we can only hold mental representations of ideas or concepts we can name.

Much debate has swirled around this theory. If it is accurate — and I am inclined to agree with it — we have only to look at other languages to see new and nuanced mental landscapes.

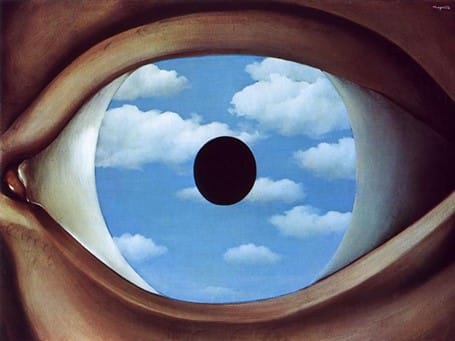

A perfect example of this is the word “cloud”.

In Lakota, the root word for cloud and sky is MA-HPI-YA.

Alter the root slightly and the word now conveys a very specific sense of cloudiness:

- A scattering of clouds (Mahpihpiya)

- The shadow created by a cloud (Mahpiohanzi)

- The passage of clouds at intervals blocking sunlight (Mahpiyouhanzizi)

- One lone cloud (Mahpiyaayaskapa)

- Black clouds (Mahpiyasapa)

- Thick clouds (Mahpiyasoka)

- Long broken clouds (Mahpiyaspuspu)

- Little white clouds scattered in just part of the sky (Mahpiyatacejiksica)

- Blue clouds (Mahpiyato)

In this example, Lakota seems a windblown language with words holding oceans of meaning.

Imagine a language with such satisfying depths where one could describe a physical and mental landscape with such precision and, furthermore, where the listener or reader would immediately visualize your depiction.

There is considerable debate on which language has the most words. Some say Korean has 1,100,000 words, but others contest this. Typically, English is considered the wordiest language. The Oxford Dictionary has documented a rough total of 600,000 distinct words, with about 171,000 in current usage. Perhaps, sadly, the average person is only notionally aware of 20,000 to 35,000 words (and we all know some who likely know far fewer, alas).

Coming back to clouds, the Lakota language likely has a smaller lexicon, but they didn’t stint on cloud coverage.

In English, the word “cloud” originated in the Old English clūd, which signifies a mass of rock or earth or a hill, akin to “clot” or “clod”. Some lexicographers believe that the Old English term may be derived from the Greek “gloutos” meaning “buttocks”.

Greek buttocks notwithstanding, a cloud was originally the ground.

One could imagine that the English, with their heavy rain-laden clouds, saw a resemblance to clumps of damp earth. By the early 14th century, the term clūd separated permanently into clot/clod and cloud.

But what did the Old English call clouds?

Here is a quote:

Næs þā nān wolcn on þǣre lyfte.

There wasn't a cloud in the sky.

They used the word “weolcen”, which is the origin of a now uncommon word “welkin”. Welkin was a perfectly understandable term, and you will find it in the writings of Wordsworth, Longfellow, Walter Scott, and Charlotte Brontë to name a few.

“Welkin” also went through some changes. Originally it meant simply “cloud” but over time it became a more figurative term signifying the heavens, the firmament, and the entire sky; it is still occasionally found with this meaning in literary contexts and regional dialects.

George Orwell believed words were important. His novel “Nineteen Eighty Four” describes the ominous consequence of reversing the Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis. In this dystopian vision, in the replacement of English with Newspeak (a language created with the primary intent of preventing the populace from having the ability to even think subversive thoughts), he effectively demonstrated how language can affect thoughts and consequently behaviours.

In his essay “Politics and the English Language”, Orwell further stated that “… the English language… becomes ugly and inaccurate because our thoughts are foolish, but the slovenliness of our language makes it easier for us to have foolish thoughts”.

Despite Orwell’s dark and ominous clouds (perhaps real but certainly metaphorical), we can still savour the billowing and racing clouds of the Lakota. In their physical and mental landscape, they clearly found clouds important and therefore created that collection of exquisite terms that give such deep shades of meaning. Of course, English has a massive wealth of words, but nowhere with such precise and intuitive language can we convey the moving shadow of a cloud across the land.

Would you like to read other posts? If so, please click the Home Page link below:

You, Dear Reader, are much needed and appreciated.

Everything written requires a reader to make it whole. The writer begins, then you, dear reader, take in the idea and its image, and so become the continuation of its breath. Please subscribe so that my words can breathe. Consider this my hand, reaching out to yours.