When AI is Wrong: An Absorbing History of Paper Towels

There are a few things I would like to cover in this essay:

- How alarmingly wrong AI can be

- The actual history of the paper towel

- Perhaps an unsung and hitherto unknown heroine in the story

- Paper towels in the United States vs the rest of the world

- Environmental impact of paper towels

My Own Paper Towel History

I only started using paper towels in the last couple years when my dogs and cat became seniors and began having “accidents” in the house.

Prior to 2024 I might have had a roll on hand “just in case”. My daughter would often complain and point out how “primitive” I was when I would use sponges or old rags to clean up spills.

With all the environmental concerns we, as a society profess to have, I've wondered why we still unthinkingly embrace this particular type of single-use disposable product and how we got there.

AI Gets it Wrong

Curious, I started with a basic Google search on the history of paper towels. Lately Google immediately provides a handy little AI summary pertaining to my request. Here is exactly what it wrote:

AI Overview

Paper towels were accidentally invented in 1907 by the Scott Paper Company when a thick batch of toilet paper was made, and founder Arthur Scott repurposed it as "Sani-Towels" for public restrooms as a hygienic alternative to cloth towels. It took until 1931 for the Scott Paper Company to introduce paper towel rolls specifically for kitchens, which then became a household staple over the next few decades as convenience grew.

The accidental invention

1907:

The Scott Paper Company received a shipment of toilet paper that was too thick to be used for its intended purpose.

Inspiration:

Arthur Scott was inspired by a teacher who had given students small pieces of paper to dry their hands to prevent germ spread.

Repurposing:

He decided to cut the thick paper into towel-sized sheets, perforated them so they could be torn off, and began marketing them as "Sani-Towels" for public places like schools, hospitals, and train stations.

From public to private use

Initial use:

The first paper towels were sold as a hygiene solution for public restrooms and institutions, not for homes.

Kitchen rolls:

It wasn't until 1931 that the Scott Paper Company introduced paper towel rolls for kitchen use.

Household staple:

Over the following decades, paper towels gained popularity in American homes for their convenience in cleaning up spills and for general cleaning, gradually replacing cloth towels.

Well…. Not precisely. It would seem that Google’s AI has merely scraped the Scott Paper Company website and ignored any other references.

Generally my expectation of AI summaries is low, and the response to my query didn't even clear a very low bar.

Many bird species feed their young by regurgitating partially digested food — and in like manner AI provides us with a convenient little information kiddie meal.

In any case, Scott's slogan "For use once by one user" and the introduction of the towel holder made paper towels a household essential, once again proving that needs can be effectively manufactured by clever corporations.

But I’m getting ahead of myself. Let’s explore the paper towel and its more accurate origin story in detail.

Who Really "Invented" the Paper Towel?

Paper towels existed long before the Scotts “invented” them. In fact (as per my non-AI research), they first appeared in June 1884 where the Queensland Herald (Queensland, as in Australia) reported:

…paper towels answer to the same purpose as cotton ones and are so cheap that they can be thrown away… the cost of washing a large number of ordinary towels is thus avoided… for removing blood from wounds, a paper towel is crumpled …into a ball and then used as a sponge.

It seems that the very first use of paper towels was intended to be in the medical field.

From Australia, the idea traveled to New Zealand. Here in January 1897, we find the following report of a “blotting paper towel” in the Eurora Advertiser: Violet town, Longwood, Avenet, Strathbogie, Balmattum and Miepoli Gazette. It comments:

The most curious use of which paper is to be put is that suggested by the recent patenting of a blotting paper towel. It is a new style of bath towel, consisting of a full suit of heavy blotting paper. A person upon stepping out of his morning tub has only to array himself in one of these suits, and in a second he will be dry.

Now the use shifted to that of drying off people (specifically men) rather than mopping up blood and wounds.

By 1900 it seems that someone in California was paying attention to news pieces from Australia and New Zealand. On September 5 of that year, the Bay City Tribune prints the same report on the “curious use”, almost completely plagiarizing the New Zealand Gazette.

From that point, several other newspapers in the United States print the same piece, for the most part verbatim.

One notes that the Scott origin story is still seven years in the future. Or not?

According to a corporate historian of the Scott Paper Company, Clarence and Irvin Scott [sic], founders of the company invented the paper towel in 1879. The Australian Gazette specifically mentions a “recent” patent from 1897. Could they have been referring to a patent filed 18 years prior? Or did some numbers get transposed? Or perhaps this was an Australian patent and therefore didn't count?

Like a dog hunting a misplaced bone, I couldn’t let this go unchecked.

It turns out that Arthur Scott (not Clarence, not Edwin Irvin — but let’s not quibble… it’s a family thing) filed a patent application on November 10, 1910 (#US1141495) which was granted on June 1, 1915. The application reads as follows (edited for highlights — it’s a VERY long application):

Be it known that I, ARTHUR H. Soon (sic), a citizen of the United States, and resident of Oak Lane, county of Philadelphia, and State of Pennsylvania, have invented an Improvement in Paper Towels, of which the following is a specification.

My invention has reference to paper towels and consists of certain improvements, which are fully set forth in the following specification and shown in the accompanying drawings which form a part thereof.

The object of my invention is to provide a cheap towel formed from paper and adapted for all general uses of the lavatory, factories, hospitals, laboratories, and for general use.

My object is to embody in the towel cleanliness and antiseptic qualities, coupled with such cheapness that the towel may be destroyed after use. The towels are preferably formed in rolls, so that only one towel at-a time may be exposed and detached, the roll form in which the towels are arranged acting to protect the unused towels from absorbing moisture and gases from the atmosphere and where a long,exposure might permit the absorption of such objectionable elements before the towel would be used.

It is noteworthy that the patent cites an improvement and not a completely new concept.

Corporate lore goes on to relate that Edwin (?) Scott was inspired by a teacher who, during a pandemic, had her students use small pieces of cut-up paper to blow their noses. The only problem with this is, again, those pesky dates. The Flu Pandemic or Spanish Influenza was rampant in 1918 — well after the patent was granted. But, corporate mythologists mustn’t let the facts interfere with a good story. Of course - and to be fair - there would have been outbreaks of flu prior to the Spanish Influenza, so the story could have been grounded in fact.

Another origin story relates that the company had produced a flawed batch of toilet paper (which predates the paper towel); it was too thick. Some unnamed employee, or perhaps one of Scott family, saw an opportunity to turn a loss into a profit and re-imagine the thick absorbent paper as a new market.

Many industrial origin stories cite happy accidents. Some more noted products that were developed from a mistake where Velcro, the post-it note (a bad batch of not-very-sticky adhesive) and conversely, superglue. A very happy accident gave us penicillin.

The true origin of paper towels is elusive, and AI’s facile summary is inaccurate. I do however think that the botched batch of toilet paper is the more likely answer.

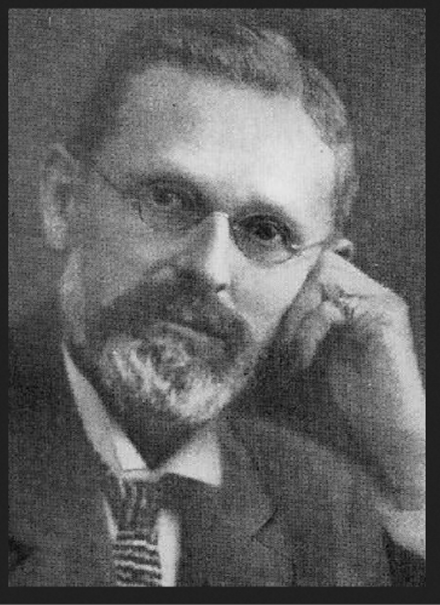

Some Scott Portraits

Let’s take a moment to explore Edwin Scott.

Actually, no, let’s not. A great deal has been written about him, so I would rather focus on one of his two wives.

Edwin was married to Sarah Frances Hoyt. Described as a pretty girl with black hair and dark eyes, Sarah — better known as “Fannie”, was the daughter of a minister. Her pregnant mother, also named Sarah, was walking in Hastings Michigan, rather near to her due date. As sometime happens, Fannie decided that now was the moment to be born and Sarah dashed into the closest building — the local jail!

In this manner, Fannie started out life a little differently than most.

Fannie became more involved in her husband’s company than would have been typical of a wife at the time. According to some, during the “panic” in the market in 1907 which almost doomed the Scott Paper Company, she addressed the employees at a company meeting, saying:

"Winter lies ahead, our men have families to clothe and feed and keep warm. For them we must strive to find some way to carry on; then if we must fail, we will all go down together."

Quite a different and enlightened message when contrasted with today’s senior management skulking off with golden parachutes.

The company got through that bad patch and continued with growing success, and eventually was purchased by the Kimberly-Clark Corporation.

Did Arthur Inspire Noam Chomsky?

As we’ve already seen from the patent, Arthur Hoyt Scott, the second president of the Scott Paper Company was the patent holder of the disposable paper towel. Arthur was Edwin and Fannie’s son and it seems fair to say he was the marketing genius that grew the Scott company into the superpower it became in the paper business.

Rather than focus on medical and industrial needs, Arthur saw the potential in — à la Noam Chomsky — a manufactured need or demand.

Classic Chomsky thought on this concept posits that to successfully manufacture a need, the product:

(1) must be designed to be limited in its lifespan or be used frequently,

(2) should have an emotional appeal beyond its actual utility,

(3) must denigrate what it replaces, and finally

(4) should create a “lifestyle” whereby the use of the product enhances the happiness of its consumer or where is improves the identity of that consumer.

At first the company still focused on men.

This advertisement from 1917 (in a Literary Digest, no less) shows their target market: heads of stores, office buildings, hotels, theatres, restaurants, factories, schools and other institutions. The “domestic” market is not yet addressed… but that will soon change.

The real leap into success was heralded by the notion that women, and not men, were the new target market.

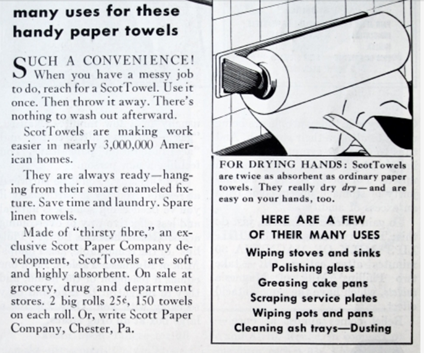

A simple glance at the advertisements from the 1930s will reveal many of the points necessary to manufacture a need.

They are positively giddy.

- You don’t have to wash them

- Pure, fresh, clean and ready

- Use it and then throw it away

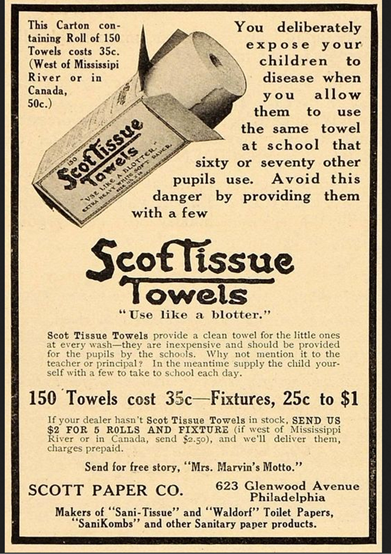

And, cleverly, they didn’t neglect parental guilt and enlisted the power of nagging parents.

Mercie Dyer Rushton: An Unsung Heroine?

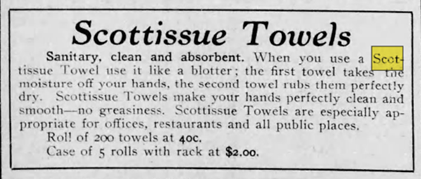

In May of 1915 the Scott company had a clever idea. In the Trenton Times, a newspaper that served the area near their Philadelphia factory, they set up a feature that was called “Paper Week”. Posing as news, but in reality an early version of an “advertorial”, the company published a full page of pieces all about Scott paper products.

Here is the interesting part: Most of the articles were written by Mercie Rushton and these pieces began circulating in newspapers throughout the United States. So who was Mercie?

Mercie Dyer Rushton (or sometimes incorrectly spelled "Mercy") was born in Philadelphia in October, 1884. She first appears in the records in a 1910 census where she is 25 years old and boarding with an unrelated family. She works as a “wrapper” in the Philadelphia Scott factory.

Within 5 years of her working as a “wrapper”, which was a factory floor position, she becomes a “stenographer” and officially continues this type of work for some time. Meanwhile, in 1915, Mercie was moonlighting as a journalist and columnist, touting the virtues of paper products in general. She didn’t always mention Scott papers specifically, but her articles usually appear near advertisements for the company.

Like Heloise of Heloise’s Hints (or more generally, Ann Landers), Mercie was there to provide insights into housekeeping quandaries and answer questions from her readers (assuming these queries actually existed).

Mercie is fond of the watchword “efficiency”. She encourages “intelligent” women to be organized and to use labour-saving devices. Cooking is now a “small matter” thanks to gas ranges, “fireless” cookers, ready-made foods and delicatessens right around the corner. Cleaning is “simple” due to vacuum cleaners. But washing… well, washing is still a tedious chore. A “bugbear” as she quaintly termed it. The way out of this toil is to use paper, and lots of it. She termed paper uses as “legion” — drinking cups (in public places), table cloths and napkins on picnics… but oh… the paper towel!

No More Drudgery, Says Mercie

It's a “labor-saver”, it’s pure, it’s simple, it touches a “soft spot”, it’s white. Its efficiency cannot be overstated. The sign of a progressive and ingenious housekeeper is a roll of paper towels hanging near the sink and stove.

When the cake is ready to bake… thick absorbent paper is torn off and used to grease the pan and then goes into the waste basket and cumbers the earth no more.

Clearly any environmental concerns are well into the future, but let's not get too far ahead of ourselves.

She suggests using several layers of paper towels upon which to drain fried foods. Clean the windows, dust the furniture, wipe the countertops, and then throw the “crumpled little wad” in the wastebasket. No soiling of clothing. No washing of cloth towels. No drying fabrics about the home. She goes on to enthuse that since all that will remain to wash are personal garments and bed linens, just send those out to a “first-class” laundry.

She touts more uses: cut glass, mirrors, windows, polish the silverware and clean the piano keys. She also touches upon the benefits to the servants, but more on this later.

So far bright and airy copy.

Mortal Danger Lurking in Cloth

In a different section of newspaper real estate, Mercie expounds on the dangers of the common towel in schools. She insists that fathers and mothers should encourage legislation to enforce the use of paper towels.

The public towel is a “menace” and children should be “warned to fear dangerous maladies”. Cloth, we are told, is at the root of these diseases: A bad cold, measles, mumps, chickenpox, whooping cough, scarlet fever, diphtheria.

It Can Make You Go Blind

Even trachoma is mentioned. Untreated trachoma led to blindness. Back then people opined that masturbation also caused blindness, so imagine if a young man used a cloth towel to clean up! Double jeopardy! But I digress.

One of Mercie's readers writes "How may I most easily avoid danger of infection from common towels?" The answer: Scott Paper, of course.

Beware of Hotel Laundry

Mercie relates a story of a lady at a Boston hotel. The woman dried her hands on a freshly laundered towel and developed a dreadful rash. But this was nothing compared to the man who sojourned at a posh Maine establishment. He dried his face on a newly laundered towel, causing his eyes to become inflamed. Shortly afterward he became blind!

A man in Camden developed a skin condition that cost him $500 (in 1915) to cure.

"Women!", Mercie exhorts, "think of your husbands, your brothers, your children!"

Only Fresh and Sweet Spruce Trees

In case anyone needs further convincing, Mercie explains why the product is sublime. It is made from only fresh and sweet spruce trees (she also adds that these trees grow in forests, but I'm unsure why that needs to be emphasized). The trees are then cut "into little pieces", and placed in a large boiler, subjected to 140 lbs of pressure (‽) and transformed into pulp. Sulphuric acid is then added to kill the "pitch" and "impurities". After rinsing the acid away, the pulp is then put into a tank with chloride of lime, which makes it "absolutely pure".

The lime is washed out using only the "purest" water — a water more filtered and cleaner than anything one might drink. The pulp is dried and a chemist very carefully examines it. Then off to a vat of "rolling knives" using more of the purest water and from there to "refining" machines to remove dirt and "lumps". Next to a screen and another machine to make thin sheets which are subsequently "thickened".

Mercie enthused:

No human hand touches it from pulp to paper.

But What About the Servants?

But what about the expense? And the servants? Well, Mercie does acknowledge that the cost of the paper towel exceeds that of a cloth, but it does save labour. After all, it is up to the mistress to teach the servant the proper way to do things — right from the start. Because, Mercie tells us, it's easier to teach the servants the right way early on rather than to correct them later.

Furthermore, Mercie assures us, every good servant would rather work for a kind mistress who takes an interest in her, rather than just offering more money. In other words, paper towel instruction is worth more than money itself, so put the money towards the former and not towards the help.

Mercie, Where Did You Go?

The years 1915 to 1918 must have been heady days for Mercie. No longer a "wrapper", becoming a stenographer, and writing copy for newspaper features, her work syndicated (of a sort) throughout much of the United States - glory days indeed.

Did Mercie write the copy herself? Or was she merely a "face" or a "name", and some other corporate menial wrote the actual words? After all, census returns confirm that she never attended high school. Was Mercie a force behind the remarkable success of this product? Was she compensated, financially or otherwise for Scott Towels meteoric rise to prominence in the paper market? Somehow I don't think so.

I don't think we will ever know.

After the First World War, Mercie all but disappears from the records. No more newspaper articles. In 1940 she is living as a boarder with a fireman and his wife. The fireman earns $1800/month, and Mercie is making $700 at a department store as a sales "girl" (she's 56 years old, hardly a "girl", but those were different times). In 1950, she's still in Philadelphia, boarding with an older single woman. Mercie is now a department store "demonstrator".

Then, in February of 1952, Mercie was doing demos at a Scranton Pennsylvania dry good stores at the "Kitchen Karnival". She was advertised (in tiny print) as a “factory expert”, touting Easyoff, Copper Brite, Mystic Foam. Sani Gleam and Sani Wax. She was 67 years old.

Mercie never married and never had children. She died at 80 years of age, alone, in a Philadelphia nursing home.

Did anyone know about Mercie's journalistic history? Did anyone realize that she had a hand to either a greater or lesser degree in forming the Scott empire?

The person reporting her death didn't even know the names of her family.

Paper Towels and American Exceptionalism

The United States status as the top consumer of paper towels is one of unquestioned dominance. According to various sources, the global use of paper towels in 2017 totaled $12 billion. The United States alone accounted for $5.7 billion of that total. In other words, the United States used almost twice of many paper towels as the rest of the world combined.

Second place goes to France at a paltry $635 million, third to Germany and a meagre fourth place finish to Italy.

Even factoring in population, the per capita use in the United States is rated at 24 kg. (53 lbs) yearly, 50% higher than Europe and 500% higher than Latin America.

According to a 2016 Nielsen report, more than 60 countries preferred to use brooms, mops, brushes, rags, cloths and sponges as opposed to paper towels.

So this, in part, explains why I don't tend to use paper towels: I spent my formative years (at least in terms of house cleaning) in Europe.

Environmental Impact

Despite Mercie's "shall cumber the earth no more", paper towels do have a significant impact.

Made from either virgin or recycled wood pulp, bleach is often used as well as various colouring agents to either brighten or decorate the end product. Sizing, or resin, is added to improve durability.

Second only to toilet paper, these towels are largely not recyclable. So not only is there the issue of the production (trees, water, fossil fuels, the plastic overwrap it is sold in), but also that of disposal. According to the EPA, the United States (in 2015) generated 7.4 billion pounds of waste (toilet paper and paper towels).

So next time my extended family bemoans the lack of paper towels in my house, I will suggest they read this essay.

And next time Google generates a pre-packaged, pre-digested response to my queries, I will carry on as in days of yore and do my own home work, thank you very much.

Oh, and let's take a moment to remember Mercie Dyer Rushton, unsung heroine of the paper towel.

Would you like to read other posts? If so, please click the Home Page link below:

You, Dear Reader, are much needed and appreciated.

Everything written requires a reader to make it whole. The writer begins, then you, dear reader, take in the idea and its image, and so become the continuation of its breath. Please subscribe so that my words can breathe. Consider this my hand, reaching out to yours.