Whatever Happened to the Hunchback’s Mummified Penis?

What a nice day for a family picnic!

Sometime during the late summer of 1976, a friend and I were rather aimlessly driving around the Friuli region of Italy. I wasn’t seeking anything in particular but was interested in seeing what had remained of the gorgeous medieval towns that had been so devastated by a large earthquake in May of that year.

And so, with no knowledge of what I was about to see, we drove into the town of Venzone.

I had wanted to visit what remained of the cathedral, and in the adjacent church grounds I saw a well maintained path cordoned off with tasselled ropes, leading to what appeared to be a completely mundane and oversized metal garden shed.

Curious, I followed the path through the entrance and found one of the most remarkable things I have ever seen. Inside the shed, hanging one by one from wooden 2x4 planks, were the remains of about 15 mummified corpses. Additionally, there was one corpse lying in a box in the middle of the floor.

All were hanging there like salted codfish. OK… if you prefer vegetables, think of an old parsnip forgotten in the back of the refrigerator.

The corpses were both male and female, the difference being only slightly discernible by the the length of the rather lovely white lace aprons that covered parts of the bodies for reasons of postmortem modesty.

Macabre? Yes. Fascinating? Absolutely.

I have no photographs of my own to show — my friend was both uncomfortable with the mummies and appalled by my intense curiosity; he pitched a small fit of strenuously whispered admonishments enlivened with stiffly restrained yet panicked gestures when I reached for my camera.

What I do have are recollections and an enduring interest in these wondrous beings.

There is some literature in English describing the mummies of Venzone, along with various internet sites, but the story I will tell you here has been resurrected from much older Italian sources. Medical reports from the 1700s and 1800s, written in florid and prolix language, provide a fascinating glimpse into the history of the mummies along with sometimes disturbing, sometimes quaintly lovely attitudes towards these miraculous beings.

The first mummy was discovered in 1647 in the burial area of the floor of the cathedral. At the time the church was moving a sarcophagus dating from the 1300s and in doing so found the remains of whom would later be called “the hunchback”.

It was determined that the hunchback (“gobbo” in Italian) would have been buried in the mid-1300s. There is the possibility that other mummies predated the “Gobbo”, as the existing cathedral was built upon another older structure, likely from the 1200s, but documentation is scarce to non-existent.

The identity of the “Gobbo” is unknown, but chances are he would have been of reasonably high social standing. Only those who were considered “important” people would have had such a prominent burial location, inside the church and near the altar.

A total of 21 tombs were located in the church, of which 13 contained mummified human remains. Of these 13 individuals, the seven located closer to the altar steps appeared to have undergone the mummification process rather quickly (in many cases it took as little as a year) from the time they were buried. It was determined that the faster the mummification, the better the preservation. All 13 had been placed under limestone slabs, and these slabs had marked porosity and fissures. In fact, when the slabs were removed, the wooden caskets were found covered in dust from the church floor.

Most of the burials took place in the first half of the 1400s.

The phenomenon at Venzone became well known in Europe in the early 1800s. When Napoleon passed through Friuli in 1807, he and his soldiers went to visit the mummies. From 1819 to 1848, several European rulers visited the cathedral.

Many scientists were greatly interested in the process that caused what was termed “natural mummification” and posited theories pertaining to moulds, fungi, chemical composition of the soil (precisely of interest were hydrogen, carbon, calcium phosphate, calcium carbonate, common chalk and other components). In fact, one group of researchers scooped up some dirt from the tombs and took it back to their laboratories, where afterwards they buried some cats and frogs (hopefully already deceased) in unsuccessful attempts to replicate the process.

After two centuries of inquiries, it was largely concluded that the combined specifics of the environment, along with the presence of a mysterious antibacterial fungus called hypha-bombycina persoon, was responsible for the mummification. According to some scientific papers, this elusive fungus may not actually exist; but assuming that it does, it is believed that it fed off the bodies, having made its way through the porous stone and wooden caskets surrounding them. The bodies likely gave off some water vapour during the start of decomposition, and within the microclimate created by the church’s foundations, the fungus would have absorbed all the ambient water that been contained in the bodies' tissues while feeding off the corpses themselves.

There are additional studies commenting upon the clothing and shrouds used to bury the bodies — textiles made mostly from absorbent and natural linen fibres. Furthermore, the church structure protected the grave sites, and the wooden caskets containing the bodies.

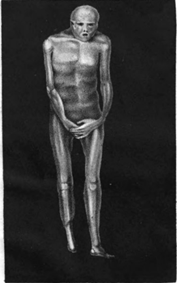

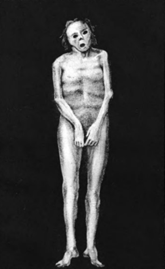

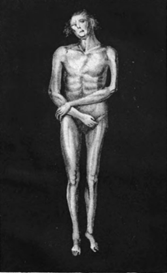

The result was the appearance of unusual yellow-grey bodies, which resembled cured leather, and were coated in a parchment-like substance. I still think they looked far more like dried salted cod, or old parsnips forgotten in the back of the crisper.

The dried skin and desiccated body parts adhered to the bones. All the internal organs had disappeared, but the lower abdomens were rather pliant. The eyelids of the corpses were open (or had opened during mummification) and adhered to the upper eye sockets (which is certainly different from ancient Egyptian mummies whose eyes were replaced with shells, linens or painted onions — you’ll never look at a martini with cocktail onions in the same way now that you know this!). Some hair remained, and the faces would likely have been recognizable to those who had known them in life.

The average height of the males was 165 cm (5’4’’), of the females 148 cm (4’8’’). Given that the desiccation process would have shrunken the bodies, the average heights make sense. Most of the mummies weighed between 10 and 20 kg (22 and 44 lbs).

The famous Gobbo (who likely died around 1340-1350) was determined to have been somewhere between 45 and 60 years of age at the time of death and was of “robust” constitution. In reality, he was not a hunchback. Upon examination of the body, post-mortem damage to the bone at the head of the spine was found. It is likely he didn’t fit into his casket and was forced into it. His ankles or feet may have been broken for the same reason. In life, he had had some broken bones in his right leg which had healed prior to his death.

He was dressed in expensive velvet clothing and was found in the Scaligeri tomb (the name of a patrician Veronese family).

Another interesting, sad and creepy detail is that he had noticeably large genitals. When Napoleon’s soldiers came calling, several of them removed bits of the Gobbo’s penis and scrotum to take home as macabre souvenirs. More on this later.

Returning to the chronicle of the mummies, by the mid-1800s more had been unearthed, and by 1831 they totalled 18 — all buried in the early 1700s. There may have been more, but it is possible that others were removed either for study or sold for medical uses. It is also possible that the church may have “covered up” any mummies found earlier, attempting to quell any dark concerns. But all this is purely speculation.

A brief detour into the medical uses for mummies: In a type of magic by association, the mystical aspect of natural (and not-so-natural) mummies led to the belief that they possessed miraculous properties. Powdered mummified remains were often added to medicines, tonics, and tinctures, and were called “mummy elixirs” or “extract of mummy”. The medical community put a particular premium on mummy powder obtained from the skull (something like protein powders sold by GNC at the mall today).

So, our 18 mummies were propped up for viewing. Finally, by 1842 a total of 34 mummies had been officially documented and placed on display.

Of these individuals, two were sent to the medical schools of Padova, one to Paris and two to Vienna.

One individual mummy, a man named Don Francesco Tomat, who died at the age of 77 in February 1826, was dug up in May 1828. It is believed he either died or suffered from hepatitis. His body was analyzed and destroyed.

In 1845, the remaining mummies were moved to the San Michele Chapel in the Cathedral, but by 1930 there were only 22 left.

In May 1976, after the devastating earthquake, only 15 remained (eight men and seven women) and those were the ones I saw in the tool shed. Today only five are viewable, sometimes fewer, with ten awaiting restoration.

Initially it was thought the mummies were only men. This was due to the notion that only those who were socially “important” would be buried inside the church. But subsequent examinations proved this wrong.

In fact, on July 28, 1876, the body of Anna Maria Verona Ferrario was unearthed. She had died in 1816 at age 26 from typhoid fever.

Here is another creepy and disturbing fact. The surgeon (named Bellina — which in Italian means “pretty girl” — such are the improbable ironies in life and death) who examined the body found it “very well-preserved in all its parts” but he was grimly focused on the wealth of black pubic hair he found around her genital area. He devotes far more excited commentary on this fact than he does to any other findings pertaining to this young woman.

I can imagine the illustrious Dr. Bellina, standing over his prize mummy, pointer in hand, lecturing before his rapt students and acolytes about the miraculous endurance of pubic hair. Ewww.

Between the French soldiers cutting off scrotum parts, medical quacks powdering the remains for sale and the “professionals” being rhapsodic over pubic hair, one can only feel profoundly disturbed.

Let us all take a moment to say the name of poor Anna Maria Verona Ferrario — a real young woman and not just a mummified repository for pubic hair.

To honour the other wondrous persons, here is my translation of the record of a visit from October 1829. Eighteen mummies were described:

The underground vault is circular, similar to the external shape of the chapel. The mummies are all naked, standing in the caskets in which they were found, and their backs leaning against the wall. This is the order in which I found them:

No. 1 — Don Antonio Martinelli, organist. Died 20 years ago in his 80s. His head is leaning towards the left as it did in life. His eyeballs are well-preserved, as are his chest and upper extremities. His lower extremities are not well-preserved and have detached from the body.

No. 2 — An unknown priest. One of the oldest mummies, with well-preserved eyeballs, bottom teeth all present, good chest and upper extremities.

No. 3 — Unknown individual, among the oldest ones given the condition of the skin

No. 4 — Another priest, “gigantically” tall, date of death unknown, poor condition

No. 5 — A priest named Mistruzzi who died in his 70s in 1727. His head is damaged, but you can still see red hair on his chin.

No. 6 — Another priest named Gattolini, died age 30. Well-preserved.

No. 7 — Another priest, also surnamed Gattolini, first name Daniello. He died in his 80s, 14 years ago and was very fat. Now his mummy is well-preserved despite having been underwater. Both hair and skin are preserved.

No. 8 — This is the mummy of the Parish Priest Masoni who died in 1740. His mummy is deteriorating, but still has his genitals and both eyes.

No. 9 — Presumably a Scaligero family member, nicknamed Gobbo. His mummy has been damaged both by the curiosity of some [we know what that means — ed. Note], and due to exposure to humidity in his lower extremities. [Note: the author remarked upon the remarkable size of the penis, and that it was still enormous and flexible, despite three quarters of it being removed by the French for souvenirs.]

No. 10 — Another priest named Sbrojavacca, died 40 years ago, in his 70s. He is “grim” and well-preserved.

No. 11 — A priest named Valetine Flamia, a doctor who died more than 70 years ago at age 27. His head is damaged, but the rest of the body is fine.

No. 12 — Don Giovanni Verona, a priest who died in 1754 from apoplexy. His mummy is worn, with his mouth folded to the right and his nose to the left.

No. 13 — Another priest, from a long time ago. He had a gun shot wound under the left armpit and died convulsed. The mouth and nose are folded towards the wound, otherwise the body is well-preserved.

No. 14 — Don Antonio Verona, 74 years old who died in 1824.

No. 15 — A priest named Pascoli, one of the last removed from the tomb.

No. 16 — Unknown individual, but some parts well-preserved. The lower extremities were removed as they were damaged by humidity.

No. 17 — Don Francesco Tomat, who no longer exists, as I sent him away for scientific research

No. 18 — Giovanni Battista Malpillero, died age 79, exhumed in February 1829 after two years buried.

A bit of morbid curiosity: Whatever may have happened to the bits of the Gobbo’s penis? According to the histories, several pieces were cut off and taken away as souvenirs. Were they sold to pharmacists or to some patron for his cabinet of curiousities? Did any of the soldiers misplace their bizarre memento? Did some bits end up in a drawer and later found by the family (as in “what in Heaven’s name does Grandpa have here”? Did the soldiers hang onto their mummy penis parts like some macabre rabbit's foot? Did any of the soldiers die in the battlefield with mummy penis in his pocket?

Yes, I'm OK, really… I was just wondering.

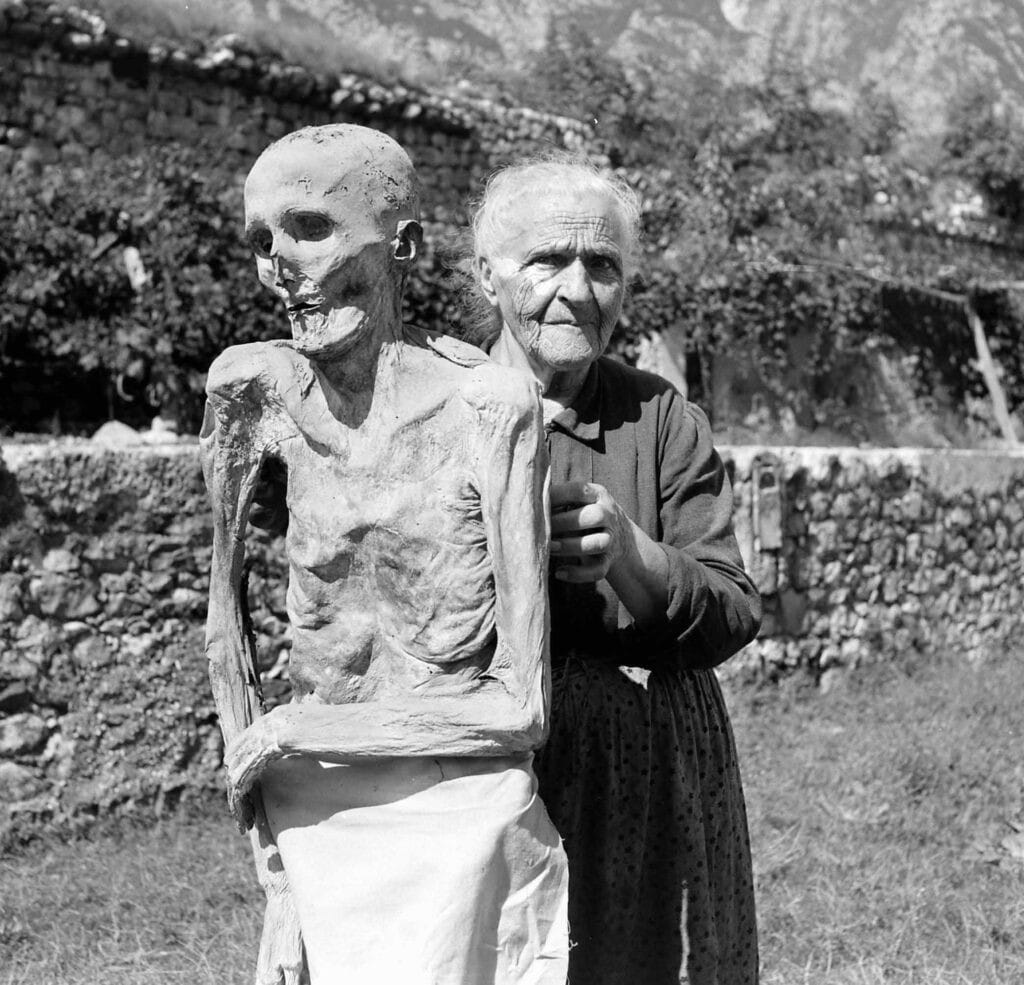

On a less morbid and more respectful note: Some wonder, when they were discovered, did the people of Venzone fear the mummies? It appears they did not. There was some murmuring of diabolical influences, but generally good sense seems to have prevailed. The townsfolk seem to respect and feel great affection for their forebears, as is wonderfully captured in the iconic Life Magazine photos from a bucolic day in 1950.

Would you like to read other posts? If so, please click the Home Page link below:

You, Dear Reader, are much needed and appreciated.

Everything written requires a reader to make it whole. The writer begins, then you, dear reader, take in the idea and its image, and so become the continuation of its breath. Please subscribe so that my words can breathe. Consider this my hand, reaching out to yours.