The Shady History of Our Family Tree: Our Norway Maple

Connecting George Washington, Jung, Micro-bursts, Fungal Tar Spots, Slavery, and Germanic Folklore

I believe you may find connections to an extraordinary amount of history simply by stepping into your yard and looking anew at what is there.

Our yard contained three Norway Maples; now only two remain. The original “mother tree”, a female — we know this because she produced “helicopter” seeds every year — is no longer alive. Her two offspring, a male and a female, are still growing, and are both seemingly hardy.

The mother maple had been planted here sometime around 1956, when the house was built, and was likely a tiny seedling in the 1940s. She grew to a towering height of roughly 70 ft (ca. 21 m), and near the ground her circumference was around 6–7 ft (1.83–2.13 m).

She was presiding over the backyard when I moved here in 1961, and was a source of shade and play for years. We made daisy chains of her leaves; tossed her helicopter seeds into the air; used her fallen branches to build forts; made watercolour “paint” from her bark; and laid beneath her canopy in the summer, staring up into the deep green.

Over decades, she was home to numerous families of squirrels and once (that I know of) to a family of raccoons. Although her progeny may have been legion, just two remain here in my yard.

An Immigrant to the New World

Her family was an immigrant one, as Norway Maples are not native to North America. Originally from Northern Europe and Asia, in her native land a Norway Maple can live up to 250 years, and grow staggeringly tall. Here in North America, my tree was as large, and as old, as can be reached by an immigrant Norway Maple.

Botanical historians have documented that the first person to import seeds of the Norway Maple was the botanist John Bartram of Philadelphia. Bartram was born in the late spring of 1699 to a prominent Quaker family. His mother died in 1701, and he was sent to be raised by his maternal grandfather. Then, in 1711, his father William was killed by natives in the Tuscarora War, and his stepmother and step-siblings were captured and held for ransom. Once redeemed by relatives, his step-family had him join them in Philadelphia.

In describing his youth, Bartram wrote “all my younger years being subject to grip, grievous coughs, heartburn, acrimonious looseness, dizziness, and rheumatism”. He was afflicted with a “slavish fear of lightening”, which leads one to wonder how skittish he might have been in the outdoors as a botanist and explorer.

Bartram, perhaps understandably given his family’s tragedy, had a poor opinion of Native Americans, and once wrote that the best way to deal with them was to “bang them stoutly”.

He was also an enslaver, buying and selling human beings throughout his lifetime and helping his son to do the same. He expressed concern that his slaves might “run away or murther” them, and was decidedly against the notion of educating enslaved individuals. Bartram did, however, speak well of one man (possibly a free-black named Harvey) who handled his business in Philadelphia “with a punctuality, from which he has never deviated”.

As a Quaker, his belief in slavery may have put him at odds with his congregation, and might have contributed to his being expelled from the Society of Friends in 1758.

As a Norway Maple, which spreads its seeds abundantly — so much so that it is considered a “noxious weed” — Bartram had two children with his first wife, and then another five in a second marriage.

But enough on his personal life. Bartram was well-known for his Norway Maple seeds —none other than George Washington ordered some from him in 1792.

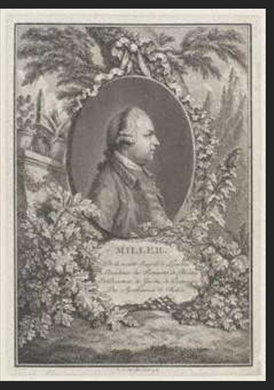

In any case, it was Bartram who first imported the seeds of the Norway Maple from England in 1756. He got them from Philip Miller (1691-1771), an English botanist and gardener.

There isn't much information, if any, on where Miller sourced his Norway Maple seeds, but every one likely originated from somewhere in Northern Europe. However, there are a few documented sources that mention the tree in England as early as 1683.

It isn't likely that my tree descends from either Bartram or from George Washington, but she would have had a common ancestry going back further in her family tree, such as a second cousin twice removed.

Is my calling my tree a “she” and referring to her family history a little over the top? To answer that question, I am reminded of a quote from the poet and essayist Mary Oliver:

“I began to appreciate … that the great black oaks knew me. I don’t mean that they knew me as myself and not another – that kind of individualism was not in the air – but that they recognised and responded to my presence and to my mood. They began to offer, or I began to feel them offer, their serene greeting.”

As with Tolkein’s Ents, I somehow imagine that trees are sentient, maneuver imperceptibly, and dream slow, thick dreams. Unfortunately, we do not understand them, and can only react to them.

One such reaction is nicely expressed by the Japanese word “komorebi”, a noun referring to the sunlight that filters through the leaves of trees.

My maple’s komorebi was dark and sparse, as her leaves were thick and numerous. My maple was a silent tree. Some are noisy: aspens tremble, as do poplars, and birches make a flickering sound. The maple is more dignified; its leaves move languidly in the wind, hardly making any sound at all.

C.G. Jung spoke of trees (and more) in this profoundly melancholic quote:

“Man feels himself isolated in the cosmos. He is no longer involved in nature and has lost his emotional participation in natural events, which hitherto had a symbolic meaning for him. Thunder is no longer the voice of a god, nor is lightening his avenging missile. No river contains a spirit, no tree means a man’s life, no snake is the embodiment of wisdom and no mountain still harbours a great demon. Neither do things speak to him nor can he speak to things, like stones, springs, plants, and animals.”

Folklore of the Norway Maple

The Norway Maple has little or no spiritual significance to First Nations people here in North America, which makes sense given that these trees arrived after the mid 1700s, and only spread significantly in the middle of the 20th century (when my tree was born). However, in Northern Europe there are traditions associated with it.

In Germanic and Central European folklore, the Norway Maple is associated with strength, protection, and the spirit world. With a lifespan of up to 250 years (in Europe, not in North America), it was considered a long-time witness to events. Its branches were placed over doors and windows, those liminal spaces and thresholds, to protect against the passage of evil. She was considered to be the über-mother of the forest. Her bark and leaves were made into teas said to strengthen the liver. Her leaves, reminiscent of the shape of hands, signified good luck and abundance being given to others.

The Death of The Mother Tree

After more than six decades presiding over my backyard, passing nourishment through her roots to her progeny; of standing resolute through subzero winters and blisteringly hot summers; suffering and recovering from fungal tar spots in her leaves; in her old age she was beset with calamities.

First, it was a terrible late spring storm, when a microburst hit her from above, followed by a terrific bolt of lightning. She had two main trunks, but one of them was sheared off, falling down with a thunderous crash. She lost about half of her body in that event. From there, weakened, she had lost her ability to withstand strong winds. She was struck by lightning several more times. Heavy snow accumulated in her canopy, causing large branches to crack and fall. Ants and fungi began to make their way under her bark skin, further weakening her. The neighbours built a starter-castle on the large lot behind our home and flooded the yard with stadium-level security lighting, interrupting what we now know is much needed darkness.

Yet occasionally, the wind still breathed through her, as a slow wave breaking on a silent shore.

Finally, she was a danger to her daughter tree (who had grown somewhat stunted in her immense shadow) and a hazard to our home. With profound regret and a heavy sensation of guilt, we had her cut down.

But not to the ground. What remains, other than her massive root system, is a tall stump, about 10-12 ft. (ca. 3 – 3.66 m) high — a standing monument to what gardeners now call a noxious weed, but what I think of as a witness, and fellow earthling.

Would you like to read other posts? If so, please click the Home Page link below:

You, Dear Reader, are much needed and appreciated.

Everything written requires a reader to make it whole. The writer begins, then you, dear reader, take in the idea and its image, and so become the continuation of its breath. Please subscribe so that my words can breathe. Consider this my hand, reaching out to yours.