The Regular

Years ago there was a regular customer at the bookshop. He came semi-monthly, sometimes weekly. For some reason I can only recall him visiting in the winter.

He wore a long leather coat, similar to those worn by exotic and eerie characters in vampire movies, or like a Gestapo officer without the symbols of the Nazi. The coat was likely of good quality — or at least had been. At the time of his visits, the leather was scuffed and worn, yet oddly rigid, as though decades of dirt had somehow bestowed upon it the quality of armour.

His tread was heavy. He wore slightly oversized boots and his trousers were tucked into their tops.

On his head was a remarkable and large fur hat which appeared similar to a Russian Ushanka, but without the ear flaps. The fur was a dark nondescript grey. He was a tall man, and the hat made him even more noticeable.

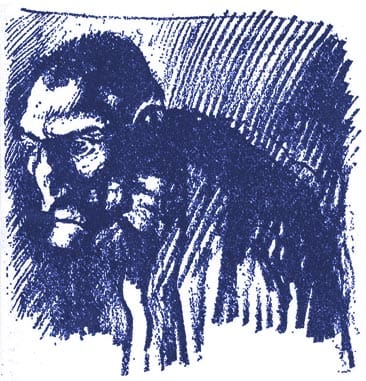

His face was almost skeletal, with rheumy eyes sunken in their orbits, a hawkish nose, and prominent bones. Upon arriving at the shop, he would begin to compose his face and mouth into the form of a greeting. But it was as though he had watched the process done by others and was unclear on how to properly replicate the movements. He had only marginal success in this endeavour. His facial muscles and bones seemed slightly out of alignment and not coordinated in their timing. He would achieve an approximation of a smile, creating a grimace, and while his face was in strange motion, I imagined the sounds of his bones grinding. He had an indeterminate accent, perhaps Eastern European, Russian or, less likely, German.

Whether he was speaking or not, his jaw was in constant slow and creaky motion. The corners of his mouth had a white pasty substance that was viscous, and expanded steadily throughout his chewing. When he spoke, the slick paste would stretch alarmingly, sometimes snapping back into his mouth. Occasionally this would be followed by a throat expurgation of so much phlegm that it was hard not to visibly recoil.

He liked history books but his selections had no particular period or discernible subject preference. He would select large stacks of volumes, bringing them over to the counter so I could tally up his purchase.

Always paying cash, he would extract a handful of bills from some deep hidden pocket inside his leather coat. His hand and arm would disappear up to his elbow inside some crevasse and he would root around until cash was located. This was before Canadian bills came to be made of plastic and this paper money was always very creased, very dirty and slightly sticky.

Once his purchase was complete, all the books — sometimes twenty or more — would be placed inside a type of wheeled carry bag, also leather, also very worn and scuffed.

But what I recall most vividly and viscerally was how repellent he was. I have no concrete reason to suspect that he was not a good man, but there lingered about him the most dreadful yet subtle odour of neglect and of uncleanliness. It wasn’t sweat, it wasn’t the stench of incontinence or of leftover food; it was undefinable yet frightfully distinct, unique to him alone. Although this is not what it smelled like, the sensation was like sniffing milk about to turn. Is it still good? Has it gone bad?

It’s as though I’m attempting to draw a scent using crayons, trying to describe the ineffable.

He would browse for what seemed very lengthy periods of time, wafting this air of confined corruption with each movement.

I don’t believe others noticed it as much as I did, or perhaps the other customers were being polite. Despite no obvious avoidance of the man, other patrons seemed to unconsciously give him a wide berth, as though he exuded some subtle yet discernible sense of something abhorrent.

I would try to breathe shallowly around him, sipping the air. I felt as though I had to go under water, caught in an undertow then coming up for air, like a series of drownings and coming to. When he would open the book bag, a whiff of stagnant water, of something old and alive yet rotten, would slowly rise, like invisible smoke curling through the air.

After he would leave the shop, there was a hint of something lingering, like the warm fog of a car recently turned off, or the sillage of perfume – but in this case, nothing so pleasant. Words fail to render this sensation — turgid, musty, and like mildew in long closed up rooms.

Never have I, before or since, encountered this sort of olfactory repulsion. Despite the odour being subtle, it somehow lingered around and after him, and I felt as though I could taste it — as if my mouth were filled with a darkness made of damp wool, a darkness so thick that I could taste and almost chew.

Zero is the decibel threshold of our hearing and we experience, on average in an urban area, around 60-80 decibels. We can detect minute levels of light. But what is the threshold of detection for odours? Some believe that we sense different smells at different levels, depending on the scent’s actual chemical makeup and the “distinctiveness” of the odour. Some research also indicates that we can sense infection and disease at an unconscious level. But can we detect moral decay? Because fusty corruption is what I sensed in this man’s presence.

Centuries ago doctors used to smell patients to diagnosis illness. Lunatics smelled like yellow deer or mice, kidney failure was indicated by ammonia on the breath, typhoid like freshly baked brown bread, measles like fresh picked feathers, scabies like mould, gout like whey, tuberculosis like stale beer, plague like over-ripe apples, and diabetics sweet like rotten fruit.

But this man emitted none of these. Nothing so mundane or definable. Being in his presence was being subjected to unwanted intimacy, as though being infused with instinctual knowledge and the ascription of immoral values. I felt a far deeper sense of ‘dis-ease’ than one would feel touching something soiled because this essence was coming into my lungs and invading my person, not merely touching the surface.

For months he was a regular customer of the shop, during which time I endured his visits. Then, suddenly, he stopped coming altogether. He was old. Perhaps he died? Moved to another area, a retirement residence?

I never knew his name. But his memory is still alive with me, lingering amorphous and inchoate, like a strange dream I am destined to remember rather than forget.

Would you like to read more posts? If so, please click the Home Page link below:

You, Dear Reader, are much needed and appreciated.

Everything written requires a reader to make it whole. The writer begins, then you, dear reader, take in the idea and its image, and so become the continuation of its breath. Please subscribe so that my words can breathe. Consider this my hand, reaching out to yours.