Pronouns of Acceptance

Firstly, I would like to thank my dear friend Frank. I came to know this remarkable man almost a decade ago and have nothing but respect and admiration for him. It should also be stated that we come from very different backgrounds (he was raised and lived in various southern states in the USA), and there is a large age difference between us. In fact, almost everything about us is different from the other.

Secondly, Frank has given me permission to use the example of his history to illustrate a point I want to make about the use of pronouns and gender fluidity.

Thirdly, let me state that I believe Frank is certainly a heterosexual male.

Here is where Frank fits in. His proper birth name is “Francisco” but he began referring to himself as “Frank” at around the age of nine while living in Georgia. The people there had trouble pronouncing “Francisco”, so he just switched to the simpler abbreviation of “Frank”. One might wonder if that the change was additionally prompted, in part, by concerns about his Latino ethnicity, but he tells me that this was not the case. It was merely convenient. It continues to be his preference, but he’s also perfectly OK to be called “Francisco”.

I don’t believe anyone said, “You were born Francisco, and therefore you mustn’t call yourself anything else”. It was his decision, and he stayed with it.

It’s a Family Affair Part One

Moving into the heart of this essay, I have two extended family members who changed their names to reflect their choice in gender identity. Of the two, one was closer in age to me, she (who was originally born a “he”), was living at a time when the current, more precise (or perhaps more philosophically aligned) pronoun of “they” was not generally an option. I won’t ever know, as she died some time ago, but I believe she might have adopted “they” as her pronoun of choice.

The other family member changed name from a feminine styled one to a more masculine variant, and actively refer to themselves as “they/their”.

I admit, being old and having decades of gender-specific pronoun use, I make mistakes. Sometimes I forget. But I do ask everyone for patience — the error is mine, and the effort should be mine.

According to Wikipedia and other sources, there are at least 90 variations in gender and gender terminology. Some are modern constructs and some are much older. But all are intended to reflect how individuals describe and present themselves; how they feel and think.

Let’s Talk Pronouns

Interestingly, in the American South they have this wonderful term: “y’all”. In the recent past I would have had a grammar-police objection to the expression; and I’ve always disliked the Canadian and Northeastern American expressions “You guys” or “Youse guys”. But “y’all” (or the slightly awkward “all y’all”) seems very inclusive, non-gender specific, and perhaps an ideal and respectful usage.

It seems ironic that a seemingly gender-neutral term has greater usage in an area, at present, not known for championing diversity and inclusivity.

I am fluent in Italian, so I am comfortable providing some interesting pronoun usages:

- “Tu” means “you” singular and informally;

- “Lei” means “you” singular and formally.

- “Voi” can be singular or plural and is moderately formal. Used more frequently in southern Italy, it also has a flavour of what in English we sometimes term the “Royal We” — as in Queen Victoria saying, “we are not amused”.

- “Loro” means “they” or “theirs”, and is not gender-specific

- “Vostro/i” also means “yours” in the formal sense, as above. But, it can be either plural and singular.

It would be quite wonderful if English had an equivalent to “vostro/i”.

But what about “Thy” and “Thou”?

“Thou” originally was a singular version of the plural pronoun “ye”. “Ye” was used to address a group of equal or superior individuals, or it was meant to address one single superior person. Very close to the Italian “Voi”.

It’s a Family Affair Part Two

What about nieces and nephews? There is a term that eliminates the gender aspect: “nibling”.

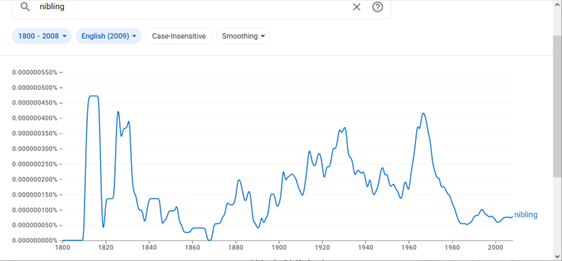

Aside from it being rather cute, the word isn’t that recent. According to some sources, it was coined by a Yale professor of Eastern Linguists named Samuel E. Martin (he was supposedly trying to create an English term for a Korean word). Some sources cite 1951 as the year the word was coined in English, but there doesn’t seem to be any hard evidence for this.

In fact, a Google Ngram viewer would seem to indicate that the word started to appear in print rather suddenly and more frequently in 1802, and peaked in that year. Subsequently, it only became relatively more commonplace in 1970. It seems odd that given the emphasis on gender-neutral language, “nibling” has now decreased in usage to early 1900s levels. On the other hand, the usage may simply reflect a spelling error of “nibbling”.

Once again, Italian to the rescue.

Niece and nephew are expressed as “nipote” for both sexes, only using the article (“la” or “il”) to denote gender.

Be Like Frank

Setting aside pseudo-scholarly considerations, why oh why do we have such a problem calling people by their names and identifiers of choice?

Even if you are personally uncomfortable with gender fluidity, that shouldn’t prevent you from respecting other people's choices. And it shouldn’t prevent you from teaching your children to be equally respectful. Furthermore, I’ve never known an individual who chooses to self-identify as a different gender take issue with referring to me as “she” or “her”. We really should extend the same courtesy we extend to my dear friend Frank.

Would you like to read more posts? If so, please click on the Homepage link below:

You, Dear Reader, are much needed and appreciated.

Everything written requires a reader to make it whole. The writer begins, then you, dear reader, take in the idea and its image, and so become the continuation of its breath. Please subscribe so that my words can breathe. Consider this my hand, reaching out to yours.