Lions Made of Fish and Shit

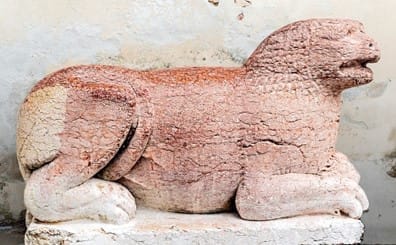

On either side of the bottom of the steps leading up to the Duomo of Treviso in the Veneto Province of northeastern Italy, lie two salmon-pink lions. They are made of fish and shit.

No one knows who sculpted these beasts. They date from the Romanesque period, likely created sometime between 1000-1200 CE.

The site of the cathedral dates to paleo-Christian times, likely as far back as the 6th century, and may have been situated near a temple (or built over a temple), a theatre and possibly some baths. As a Roman Catholic Church, it was dedicated to St. Peter the Apostle.

In the 11th and 12th centuries it was extensively rebuilt in the Romanesque style, and what we now see at the front of the building is a neo-classical revision that was done between 1760 and 1782. The steps leading to the front entrance were added in 1836 and it is there that the lions lie.

The building itself and the structures around it are mixtures of styles and periods, with flying buttresses off to one side, a baptistery, a bell tower, and a crypt.

The baptistery of St. John the Baptist predates the structure of the church itself but underwent renovations in the 1300s after earthquake damage. The bell tower is attached to the structure and remained incomplete. According to local legend, Treviso’s Venetian overlords would not allow the tower to be higher than that of St. Mark’s in Venice and so it remained only partly finished.

Romanesque lions were quite popular and were usually placed near external doors, filling the role of symbolic guardians, thus providing tangible evidence of force watching a sacred space. They were also used in a didactic sense, a symbol of ecclesia universalis, a warning against sin and a strong image of the power of God. There is also an interesting medieval legend that explains the connection of lions to the resurrection of Christ. It was believed that lions were born dead and would come to life only after their fathers would breathe life into them on the third day.

Originally these particular pink lions were likely flanking the front portal and must have been moved to the bottom of the steps in the 1830s.

The lions appear to be female (given the lack of manes), and are lying down with their tails curled around them, front paws comfortably extended. One is holding down a serpent of sorts that has its head turned backward in a attempt to bite the lion’s breast; the other grasps a representation of a human head. Both lions appear alert but non-threatening. Over the years, having been touched, stroked, ridden astride and sat upon by thousands of people, they have become smooth, silky and shiny.

As they don’t look very realistic, it is often assumed that artists from the Romanesque period had never actually seen lions, sculpting or painting them based on other works such as bestiaries or from sheer fantasy. However, lions were being kept in Rome by the Pope as early as 1100, were being imported from Asia and Africa, and were also being bred at courts. It is just as probable that the likeness rendered in art was done symbolically, where realism was not as important as the message.

Our pink lions (like many others from the same period) were carved from Verona red marble quarried from an area called Monti Lessini in the lower Alps just north of Verona. This marble owes its tint to the presence of impurities in the limestone, namely hematite (iron oxide) and feldspar. This particular Italian marble was formed from the fossilized remains of ammonites, belemnoidea, and fecal pellets - limestone, with crushed fish and shit.

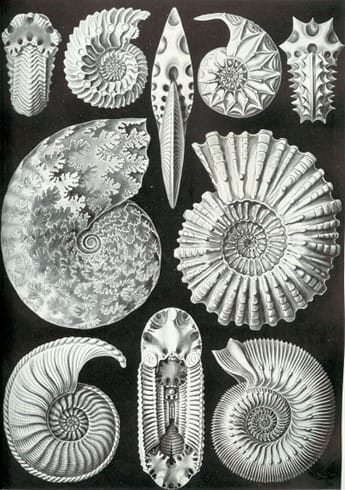

Ammonites were marine mollusks, related to today’s octopus, squid and cuttlefish. The ammonites in the lions range in age from the Devonian period of 400 to 200 million years ago, to the Cretaceous, up until the Paleogene Extinction Event that took place 66 million years ago, when three quarters of all plants and animals in the world perished.

The name “Ammonite” refers to the spiral shape of the fossilized shells, appearing like coiled horns. Pliny the Elder (who died in the Vesuvian eruption in 79CE) called them “Ammonis Cornua” meaning horns of Ammon (or Amun, an Egyptian horned god). Ancient Romans believed that if you slept with an ammonite fossil under your pillow, your dreams would predict the future.

Did the Ammonites dream, I wonder?

These distinctive fossils were also called snakestones or viper’s stones, as people believed that they were the petrified remains of coiled snakes. There are also religious beliefs around snakestones associated with St. Patrick driving the snakes from Ireland and of St. Hilda ridding other lands infested with snakes by turning them into stone.

These ammonites could be relatively small, measuring 9” in diameter (like a dinner plate), or quite large. In Germany they reached sizes of 6-1/2 feet in diameter – think of a large hot tub.

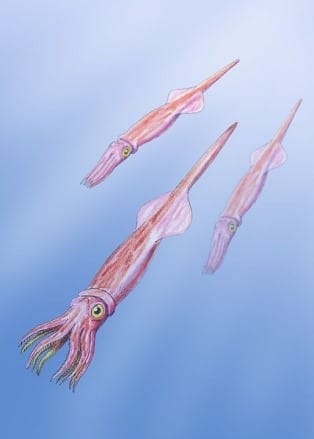

They were not bottom dwellers. They jetted or propelled themselves through the ancient ocean, feeding on plankton and squirting ink at their predators.

The other component in the pink lions is Belemnoidea - marine cephalopods, again akin to squid or cuttlefish, but their shape was more streamlined like a modern squid. They too shot ink at predators and had arms rather than tentacles. Their name comes from the Greek meaning “form of an arrow”. These creatures were the cousins of the ammonites, and ranged in size from 18” to 10 feet long.

Their fossil remains generated different legends and were sometimes called thunderstones. People believed that the bullet-shaped fossil in the rock was made when lightning struck the ground. All over the world there are beliefs that thunderstones bring good luck, and in Italy they would be hung around children’s necks to protect them from illness and the evil eye.

Can we imagine these odd squid-like creatures, darting through the sea, along with their nautilus-shaped cousins? We now know that squid, octopus, and cuttlefish have unusually high intelligence and are known to use displays of skin colours, patterns, textures and luminescence to communicate with one another. Could these unbelievably ancient swimmers have communicated in a similar fashion?

Over time, and certainly by the period of the mass extinction, these wonderful creatures all became extinct. Their soft bodies liquefied inside their exoskeletons, and those harder parts settled deep into the bottom of that primordial sea. Oxygen levels were low there at the bottom, creating the perfect environment to preserve their bodies as fossils.

Over the millennia, these creatures died and settled to the muddy bottom of this vast ocean. They, and other creatures, dropped their waste too. This fossilized shit is more politely known as coprolite (when larger and having form), or fecal pellets (when much smaller and unformed).

The bottom of this ocean, filled with the skeletons and waste of ancient creatures, was subject to tectonic movements. Over the millennia, the sediments at the bottom of the sea were pushed up into the Alps. There, mixed with other “impurities”, Verona red marble came to be.

We don’t know the name of the sculptor who created these time-worn lions. Even if he had signed his name somewhere, it would likely bring us no closer to knowing him. Was he a master stonecutter? How did he acquire his massive chunks of marble to carve? Did he have apprentices? How long did it take to release these oddly figured lions from the stone? Since there are many other pink lions in northern Italy that were made around the same time, did the artist travel to ply his trade? How was he paid? Who paid him? When he was done, can we imagine him standing back from his creations, his strong hands dusty from stonework, contentedly surveying the outcome of his work? Did he believe that the lions would remain there for hundreds of years?

I doubt he knew his lions were made from fish and shit.

What a strange twist of fate that one of the lions is subduing a serpent, when she herself is born of snakestone.

It seems oddly fitting that pink lions in front of a cathedral in northern Italy would be a part of a chain stretching for eons. Strange fish darting and propelling themselves through an unknowable ocean, sinking slowly to the bottom next to the excrement of many others like them, soft bodies and organs rotting; then massive pressure and build up of rocks that permanently etch their outlines into limestone. The limestone mixes with iron oxide and feldspar, giving birth to pink marble. The marble rising slowly over the millennia, from the lowest depths to the peaks of the pre-Alps until men begin to quarry the stone to create art. The art then becomes a symbol of the Church, two lions standing guard for 800 years, where they become smooth and shiny from the touch of hands of thousands of people, including me.

Would you like to read other posts? If so, please click the Home Page link below:

You, Dear Reader, are much needed and appreciated.

Everything written requires a reader to make it whole. The writer begins, then you, dear reader, take in the idea and its image, and so become the continuation of its breath. Please subscribe so that my words can breathe. Consider this my hand, reaching out to yours.