John Collier: Florida Pioneer, Cracker and Polygamist

John Collier Sr. was certainly a fascinating man. A true Florida pioneer, he was the personification of a “cracker” — but in the positive historical sense (more on the “cracker” origin story follows). As we shall see, his personal relationships are legion and deeply tangled.

Let’s call him “John” from this point forward and tell his story.

Why Write About John?

John had at least three wives (with some overlap in the dates of the relationships) plus a common-law spouse, resulting in 18 to 19 children (likely more)[1], many of whom had large families themselves. All told, it is almost a certainty that he has hundreds of descendants and that many people walking around today can legitimately call him their ancestor.

And, as recently as 2025 — in fact about 200 years from John’s birth, a new baby girl was born - his newest descendant.

In addition to his genealogical contribution to the world, he lived in an interesting time and his experiences, although unique in themselves, provide a glimpse into a world long gone.

Before getting into the history of the time, let’s place John in context.

John was born sometime between 1815 and 1823, most likely in Georgia, and possibly in Dooly County, Georgia. Located in the central part of the State, the population of the county was just over 2000 individuals in 1830 as per the US census taken that year.

The 1830 US Federal Census for Georgia lists several Colliers (also variously spelled as Colier, Colyer, Collear, Kolyer). It lists several individuals named William, John, Robert, Meredith, Morrel, Tahos, Benjamin, Edward, Edwin, Henry, Isaac, James, Jesse, Nathaniel, Richard, Sarah, Sterling and Thomas.

Some privately published family histories assert that John’s father was named Henry[2] and that his mother was a woman named Nancy Bird (or Byrd), but there is no documentation to support this. Equally dubious is that his mother was named Esther or Easter Turner (although the name "Easter" appears among his descendants). What is however quite likely is that he had an older sister named Piety Collier. Some records state she was born in Camden County Georgia, perhaps a few years before John.

Let’s assume for now that John was born in 1820. In his late 30s, in 1859, along with his own household and several extended family members, he made the trek from Georgia into the wilder country of northern Florida. The date of 1859 is cited in several family histories about the Colliers, but, as we will see further into this narrative, he and that large family may have made the move much earlier.

According to family histories and mentions from other sources, John (with his own family) along with his married sister Piety Crews (and her nine children[3] — although this is improbable; see below) loaded up their possessions into oxcarts and began the arduous trek into Florida towards what is now Hardee County.

There is a problem with the date and the number of Piety’s children who made the trek to Florida. According to birth records, Piety’s first three children were born in Georgia, and her fourth child, Charles Carney Crews, was the first one born in Florida in 1844.

Also, in the 1850 census, one of John’s children, Calvin Collier, was living next to Piety’s family and he had two children, the eldest Sarah born in Florida in 1844.

Based on census records, it is more likely that John and Piety’s families made the trek sometime between the late 1830s and 1844.

The two clans traveled over sandy trails, bogs and miles of absolute wilderness. Wanting to establish themselves as cattle ranchers, the men would have ridden on horseback, driving their cattle along with some herding dogs. The women would have cooked sweet potato and corn brought from Georgia and likely supplemented their meals with wild turkeys and deer shot in the forest, scrubs, and marshes.

After a little more than a week of traversing the countryside, John and the others arrived at Fort Hartsuff (not to be confused with Fort Hartsuff in Nebraska). There lived some relatives by the name of Whidden who had homesteaded in the area at a point just northeast of today’s Wauchula, near where the Heard Bridge crosses the Peace River.

Florida: The Original Wild West

Domestic cattle and horses were not indigenous to the Continental United States. It was in 1521 that they arrived with Ponce de Leon who had tried to establish a colony in southwest Florida. The native Calusa tribe didn’t extend a welcome to the Spaniards and attacked them; so Ponce de Leon abandoned the idea of settling the area and his Andalusian stock were left behind. These animals went feral, eventually becoming the ancestors of the wild cattle that became part of Florida rancher history.

And so began the “modern” history of Florida and its ranchers. St. Augustine (arguably America’s first city) was founded in 1565 and this was where the local population began raising herds for both the garrison and a few growing towns. In the 1600s, Florida’s local missions began more intensively raising cattle; in fact they began exporting beef to Cuba.

Meanwhile, the local Seminole tribe was displeased with the encroachment of the Spaniards and drove out almost all the European settlers during the 1700s. At this point it was the Seminoles who became the primary Florida ranchers and developed a method of allowing huge herds to roam wild in the wetlands, as well as in the palmetto plains and grass prairies.

By the 1800s, Florida was the center of ranching in the continent, and this attracted more settlement from the nearby southern States, and particularly Georgia.

The demand for beef increased exponentially with the onset of the Civil War, and accordingly so did ranching. Initially these Floridian ranchers provided beef to the Confederate Army, but as the finances of the South diminished, the Floridians found a more lucrative market with the Union forces. In fact, Florida had a large number of Union towns, Union sympathizers and Union soldiers. But that is another very long and involved story.

John Collier was a “Cracker”

Nowadays, the term “cracker” is derogatory, often referring to a poor white man who is poorly educated. The word conjures a picture of lackadaisical families scratching out a marginal existence with worm-ridden children running about barefoot in the swamps.

According to the Century Dictionary, by 1766 “cracker” was used in the Southern U.S. as a derogatory term for:

"one of an inferior class of white hill-dwellers in some of the southern United States".

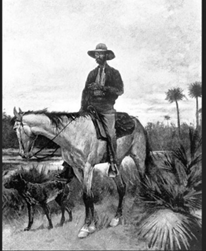

But this is not the complete origin of the term. Particularly during the Civil War, Floridian cattlemen had to drive huge herds to market and, unlike their later Texas counterparts with their lassos, they used a particular kind of whip. These whips were part of an inherited tradition from the original Spanish vaqueros. The whips were from 12 to 18 feet of braided buckskin that was fastened to a handle about 1 foot long. These special whips made a distinct cracking sound, likened to that of a gunshot, and could be heard for several miles. And so we have the original name for the country’s first cowboys: crackers.

The Peace River Valley

The area where John took his family had been a rather inhospitable place in the early 1800s and at that time was largely unexplored by the white population. Other than a few forts and a trading post, there were no white settlements and most of the land was occupied by the Seminoles (and other related tribal groups). There had been skirmishes and conflicts as the whites further encroached into Seminole land. Many died on both sides.

By 1850, in John’s time, what few Seminoles that had remained in Florida were pushed into the interior where the land was far less desirable. By 1854 the US Government made an agreement that the Seminoles were to remain south and east of the Peace River. Settlement immediately south of Fort Meade and west of the Peace River was then opened to white migrants; and so began the flood of migrants from northern Florida and southern Georgia.

Around this time and until the late 1880s, the area was home to tens of thousands of wild cattle[4], all of whom had descended from the ancient Spanish herds. Consequently, between the time of the Civil War and the end of that century, the Peace River Valley could be imagined more like a true “Wild West”. Cattle and hog thievery were rampant; one of John’s descendants (John Junior) and member of the Crews’ clan had been involved in a lurid murder that began with some stolen hogs, but that is another (certainly colorful) story.

Cattlemen like John were forced to hire rustlers to keep track of their herds (ironically the herds that had been stolen from and abandoned by the Spanish and the Seminoles), and branding became an absolute necessity. John and his family had several registered brands. Still, thieves were certainly creative, and many cattle arrived at the market with their ears cut off to prevent their identification.

John and his fellow crackers, decades before Texas cattlemen, would spend weeks or months on cattle drives, moving their herds through marshes and woods, going from central and northern Florida to the ports of Jacksonville, Savannah Georgia and Charleston South Carolina. The trail would have tested their endurance, having to deal with terrible heat, frightening thunderstorms and dangerous hurricanes, not to mention panthers, wolves, bears and other rustlers.

There was a huge demand for meat, so buyers at the markets didn’t look too closely into the cattle with severed ears. Even if there was some legal method to trace ownership, justice was rarely formally pursued. The ranchers, like John, would therefore take the law into their own hands.

Family and clan banded together (like the Coller/Crews/Whidden clan), and enforced their interpretation of the law — The Cracker Way. Unsurprisingly, this created long lasting feuds, brawls, gun fights, bushwhacking snipers and lynchings. In fact, one of John’s descendants was lynched by a mob, but there seems to be no record of why it occurred.

Here Come the Colliers and the Crews Clans

There is some confusion on the dates of John’s migration to Florida, but what is rather well documented is that his sister Piety, along with her husband Dempsey Crews, arrived in about 1844-1845. They originally settled in the Lake Butler, Lake City area, staying there until the end of the last Seminole War (in which the Crews men participated) in 1858.

Come 1859, Piety and Dempsey, along with their nine children (so far), packed up their belongings and headed south towards what today is Hardee County. It was during this trip that they may have been joined by John and his large family.

As mentioned earlier, the Colliers and the Crews arrived at Fort Hartsuff after about one week on the trail. For a short time they all camped on the land held by the Whidden family (kin of the Crews).

This area (Fort Hartsuff and Fort Green) had only been recently opened to white settlement, but already there were around twelve families there. Despite the agreement with the Seminoles, where the whites were not supposed to settle south of east of the Peace River, a family named Thompson had already violated the agreement and had settled near Popash. John and his Crews kin saw no reason why they should be bound by any government agreement, and so they continued on to settle near what is now Zolfo Springs.

And so, despite treaties, John and his relatives became the first pioneers of the area.

John and the Family Settle In

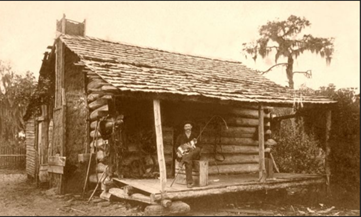

In the early 1860s, John and the Crews developed a sprawling homestead south of the Peace River. They built log cabins and created fenced pens for their cows. They planted sweet potato and corn, and they also cultivated a small amount of sugar cane and had a patch of cotton. They had chicken, hogs, and most importantly, cattle.

Let us imagine for a moment the population of this family settlement. John had at least 18 children, and his sister 17. His son-in-law had 14. And, over time, other branches of extended family would join them on this land.

But there were more people there.

We don’t know for certain if John had slaves, but his sister did. She brought eight slaves with her — a 35-year-old woman named Hagar[5] along with her seven children. One of these children may have been Richmond Crews (b. 1841) who later married the divorced or separated Irene Collier Crews (see note [1] below). The Whiddens also had two slaves.

Sometimes today we imagine slaveholders only as wealthy landowners (think Scarlet O’Hara in Gone with the Wind) but that was often not the case. John was no aristocratic Southerner, and he was most certainly working class. Not many families in the area were slave owners, but those who were tended to have only a few, and primarily only women.

The Civil War Begins

In 1861 the war between the North and South began, and John, like most of his neighbours, was either a Union supporter or didn’t care. Most of those in the area did whatever they could to avoid mandatory service to the Confederacy and hoped to wait things out. In any case, the cattle business was severely affected by the war and, in 1863, Fort Myers was seized by Union forces.

John’s family, along with the Crews and the Whiddens all enlisted in Company B, Second Florida Cavalry for the United States Army.

After the Civil War, trade normalized, and a boom began. Florida became the leading cattle exporter of the United States, sending cows to Cuba, Key West and Nassau.

And John was right there, making money and providing for his large family.

John’s Personal Story

John, his movements, and his marriage(s) are hard to follow. He moved around, had several relationships, and had many, many children.

Aside from census returns, he was documented by Kirk Munroe, a relatively famous adventurer and reporter. Munroe was on expedition in 1882 along the Kissimmee River and ran into John at a location called Basinger while John was moving from Brevard to Manatee County. An entry in Munroe’s diary from February 19th reads

“Old man Collyer [sic] with 3 wives and 14 children came over the river with teams (presumably horse, oxen or cattle) moving to Charlie Apopka Creek. They are camped near the house.”

On February 20th Munroe wrote:

“John M Pierce and Mann went with Collyer to Istokpoga Creek today and on return reported a steamer in site of Micco’s Bluff”.

Although these are only two lines, and brief ones at that, they do place John in specific places at specific times, and John must have made some sort of impression with Munroe.

Perhaps it was the three wives and 14 children.

Was it Adultery, Bigamy, Trigamy, or Polygamy?

In November of 1885 the County Circuit Court of Manatee charged John with adultery.

A woman named Samantha Jacobs swore that she

“knows that Collier does not live with his wife and a woman named Minerva Crawford visits at the Collier place. The same Crawford has six children and claims that John is the father of four”.

Miss Jacobs also said she

“has one child and John Collier is the father”.

She went on to testify that John

“induced me to live with him under the promise of marrying me when he obtained a divorce from his 1st wife”.

It’s complicated.

That year (1885) in the Federal Census we find Minerva Crawford living in Florida as a head of household with six children and at least one child appears to have been fathered by John: Virginia (born 29 January 1875).

The outcome of the court case seems lost to time, but what is certain is that Samantha Jacobs must have forgiven John; and rather quickly at that. They married on February 18th, 1886, just a couple months after the court case. The two had at least one daughter named Dora Collier (Hall?) who later recalled living with many children about four miles west of today’s Avon Park.

The Women in John’s Life – and all those Children!

We already know a little about Minerva Crawford (presumably the mistress or common-law spouse), and Samantha Jacobs, and we shall look further into their place in this narrative.

Meanwhile, who was John’s first wife, and who might have been his second wife?

Caroline Luiza Hall

The probable first wife was a woman named Caroline Luiza Hall who was born in South Carolina, likely around 1823. They were possibly married around 1840 in Georgia. Her ancestry is largely unknown. Some speculate that she was the daughter of Instance Hall, but this is almost certainly incorrect.

Carolina Luiza was living in Florida in 1850 in District 7, Gadsden, Florida, USA along with children listed as “Green, Nancy, Calvin, Irene, John and Sarah”.

She was alive and living with John in 1860 in Township 9 Range 13, Lafayette, Florida along with 9 children ranging in age from 9 to 14. A middle child, John Jr, is the first one born in Florida in about 1850.

The children are listed as: Wm G (no age given), Mary E. (14), Colvin (13), Serena (12), John (10), Sarah (8), Catherine (7), James B. (no age given), George M (1 – born in 1859)

It is also possible that Caroline Luiza was a black woman.

Caroline Luiza more or less disappears from the records and possibly moved away from all the extended and tangled family.

Mary Lockyear

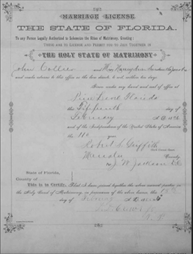

On October 9th 1869 John married Mary Lockyear, Locklear or Locklier. Mary was born in South Carolina or Florida between 1843 and 1846.

In 1870 they are living in Township 34, Manatee, Florida with 6 children, her older sister Eliza and an 18-year-old mulatto named William Perry.

In 1880 she is living with John in Brevard, Florida, along with 5 children: George Colyer (23), P.E. Colyer (son, 15), Alice (10, Nancy (8) and E.G. (daughter age 6)

The gap in age between John and Mary is substantial.

Some records indicate that she died in Florida in January of 1886.

Samantha Jacobs

Finally we come to the youngest of John’s wives: Nancy Ann Samantha Mary Mandy Jacobs. Born in Echols, Georgia in August of 1856, on the 18th of February 1886 she married John (a widower of one month).

Less than seven months later, she gives birth to their daughter, Dora Lee. She may also have been the mother of Calvin Perry Collier who was born in 1884. Finally, their last child together, Berry Henry, was born in 1888.

Perhaps slightly prior to John’s death, Samantha married Matthew Talley in August of 1896. She had three more children with Talley, beginning with Ludy Daisy born in January of 1897, followed by Charles in 1900 and James in 1902.

It would appear that Samantha outlived all John’s women, as she passed away in 1937.

Minerva Crawford

Minerva Crawford, the “other woman” named in the lawsuit, was born in Florida in 1848 to Emanuel Jesse Crawford and Martha Whidden (of the Whidden clan associated with the Colliers and Crews families).

Her two children with John were supposedly Jennie born in 1874 and Estella born in 1872. She also had a relationship with a man named Wells Murphy, a North Carolina man born in 1826 and married to Sarah Whidden (yes, the Whidden clan again) and from whom he had six children born between 1869 and 1879 (including a daughter with the improbable name of Pocahontas). Prior to his marriage to Sarah, he had been married to her sister Martha Ann Whidden (1832-1868) with whom he had nine children between 1851-1868.

Minerva had one child with Wells, William Henry Crawford (1869-1942).

John is No More

John died sometime between 1892 and 1897 and his will was dated January 6th of the former year. In it we find mention of some of his children: Green, Elizabeth, Calvin, John Jr, George, Bryant, Pleasant, Isabelle, Martha, Perry, Dora and Berry.

He was buried in the Bowling Green Cemetery in De Soto County Florida but it is worth noting — and consistent with the inconsistencies of this life — that the tombstone inscription has some erroneous dates on it.

His estate was valued at $15,000. Not a princely sum, but not too shabby either; that amount might be close to around $600,000 in today’s currency. Likely a very far cry from his more humble Georgia origins and certainly an improvement from his assessed estate value in 1860 of $100.

[1] John Collier’s children are as follows:

1. William Green Collier, born March 22, 1840-43; died Feb. 16, 1920; married Mary Ann Wiggins, July 8, 1869.

2. Mary Elizabeth Collier, born 1842-43; married ______ Green.

3. Calvin C. Collier, born June 22, 1842-43 according to pension papers; died Aug. 17, 1922; married (1) Katie Parnell, Oct. 11, 1866; (2) Beulah I. Whidden Sparkman, Oct. 10, 1897.

4. Irene Collier (sometimes called Serena, Irena or June, born 1845-47; married (1 - 1850) Lewis Jenkins; (2) Richmond R. Crews, Oct. 9, 1869. Crews was a former slave of Piety Collier Crews (Mrs. Dempsey D. Crews, Sr.). Irene was also a convict in a Florida penetentiary in 1870.

5. John Collier, Jr., born June 22, 1846 according to pension statement; tombstone has June 22, 1853 but must be in error; died Feb. 1, 1934; married (1) Sallie Lewis, Dec. 12, 1865; (2) Mattie Kemp, Oct. 16, 1902; (3) Letitia Guest Skipper, Jan. 2, 1915.

6. Henry “Bunk” Collier, born Dec. 25, 1855-56; died July 17, 1920; married Ann Gillespie, Sept. 25, 1872 (in 1885 Manatee County census his wife’s name is given as Texas).7. James B. Collier, born 1857.

8. Catherine Collier, born April 20, 1858 according to Bible but could be as early as 1853.

9. George M. Collier, born March 18, 1859 according to Bible but tombstone has 1858; died Aug. 11, 1937; married Mrs. Susan North, Nov. 22, 1883.

10. Wiley Bryant Collier, born June 18, 1860 according to Bible; died Jan. 4, 1921; married Jane E. Whidden, May 12, 1881.

11. Ellen Collier, born Jan. 18, 1862 according to Bible.

12. Pleasant E. Collier, born July 22, 1864 according to Bible; died ca. 1918; married Rachel Jacobs, Nov. 27, 1885.

13. Alice Collier, born Aug. 1, 1870 according to Bible.

14. Isabelle Collier, born 1872; married Joseph Hall, Dec. 22, 1891.

15. Martha Collier, born May 28, 1874, according to Bible.

16. Virginia Collier, born Jan. 29, 1875; married Jefferson Davis Thompson, April 17, 1893.

17. Perry Collier, born Jan. 31, 1884.

18. Dora Collier, born Sept. 3, 1886; married _____ Hall.

19. Berry Collier, born March 3, 1888.

[2] John’s sister Piety named her firstborn son Henry Collins (Crews), which would give some credence to the father’s forename being “Henry”.

[3] Piety and her husband Dempsey Dubois Crews had the following children: Henry Collins (1936-1874), William Madison Micazah (1841-1922), Elizabeth (1843-1916), Charles Carney (1844-1917), Dempsey Dubois (846-1895), Lydia Bea (1849-1920), Willis (1852-1944), Crawford (1856-1911), John Bryan (1857-1911), Mary Irene (1858-1918), Willoughby (1862-1870).

[4] These wild cattle were prized for their hardiness and resistance to parasites, and became the ancestors of the modern Texas Longhorn.

[5] Interestingly and almost prophetically (given the later miscegenation within the family), in the Old Testament Hagar was the Egyptian servant of Sarai (later Abraham's wife, Sarah) who became Abraham's concubine and the mother of his firstborn son, Ishmael.

Would you like to read other posts? If so, please click the Home Page link below:

You, Dear Reader, are much needed and appreciated.

Everything written requires a reader to make it whole. The writer begins, then you, dear reader, take in the idea and its image, and so become the continuation of its breath. Please subscribe so that my words can breathe. Consider this my hand, reaching out to yours.