Islands of Genius in a Sea of Ordinary Life

In the 5th hour of the 5th day of the 5th month of the 5th year of this new millennium my mother died.

Perhaps she was making it easy for me to remember. Nonetheless, she would have liked the numerical symmetry of it. Her interior or innate wiring was a bit extreme. Let me explain.

My mother was something of a savant.

sa-vant sə-, -ˈväⁿ; sə-ˈvant, ˈsa-vənt

a person of learning. especially: one with detailed knowledge in some specialized field (as of science or literature) or a person ... who exhibits exceptional skill or brilliance in some limited field (such as mathematics or music)

— Meriam-Webster

I think of her as having a bit more of the second portion of the definitions. She was certainly a gifted musician and she had uncanny abilities in mathematics. It is about her odd mathematical abilities that I wish to relate.

Ever since I can remember, my mother had been counting things. Not just things that one might normally count, such as how many intersections until your destination is reached or how many crows are roosting in a tree. No, she counted off random things. When she was quiet and didn’t know anyone was around, you could hear her counting softly, usually in French. I never knew what was being counted, or remembered, or solved. If I asked her, she would just brush off the subject, either because she was unaware of her activity or because she didn’t want to discuss it.

She counted the number of stairs in every stairway she climbed. Furthermore, she remembered the count from each and every stairway she ever counted in her entire life. Later, as a teenager, I doubted her accuracy and so asked for the count details from various locations. I then went to every one I could find (in particular, I remember re-counting the steps in the Royal Conservatory of Music in Toronto, which had an odd number of risers) and discovered that she had been absolutely accurate. Every time.

Birthdays were another miracle of memory. All she needed was to be told once and it would be remembered forever and immediately retrievable upon request. Even if the person was not a particularly close friend, just a random individual, she would remember. Again, I doubted, rechecked whenever possible. She was never wrong.

Number games and quizzes were something she enjoyed. Multiplication tables were simply in her head; there they resided, ever ready for any occasion, and no calculator was needed (at least up to multiples of 24, and perhaps beyond).

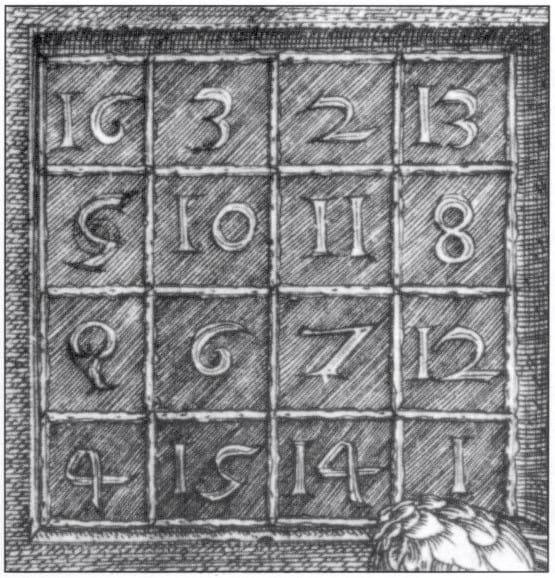

She liked solving magic squares. Dating back to the 6th or 7th century BCE, a magic square has the sum of every horizontal and vertical row as well as that of the two diagonal rows being identical. In typical puzzles, a few of the squares already have numbers in them, so the person must solve the puzzle by placing the remaining (unique) numbers in their proper places.

A 3x3 square presented absolutely no challenge to her, and she would fill in the missing numbers by merely glancing at it. At the 6x6 level, she might take close to a minute to solve it. She would stare at the square and then quickly fill in the numbers all at once.

She also had a peculiar knack for reversing numbers, finding odd mathematical facts or tricks — something like a parlour game for the mind.

A talented musician with degrees in piano performance and teaching, she would often look at or read a piece of music (without needing to play it) and comment on whether the mathematics of the piece worked well, whether there was within it some numerical stridency, or if a chord was somehow “off” and didn’t “agree” with the rest of the piece. She primarily loved classical music, but also relished jazz and syncopation, which likewise seems to have an affinity with mathematics.

These odd abilities did not get passed onto me, her daughter. I have no gift for numbers, only middling musical skills, and have no memory whatsoever for dates.

When she died at such a numerically precise time, it would be easy for a math imbecile like me to remember, and I think she must have been pleased.

Would you like to read other posts? If so, please click the Home Page link below:

You, Dear Reader, are much needed and appreciated.

Everything written requires a reader to make it whole. The writer begins, then you, dear reader, take in the idea and its image, and so become the continuation of its breath. Please subscribe so that my words can breathe. Consider this my hand, reaching out to yours.