Fireflies, Mermaids and Skeins of Thread

Folktales from the Euganean Hills

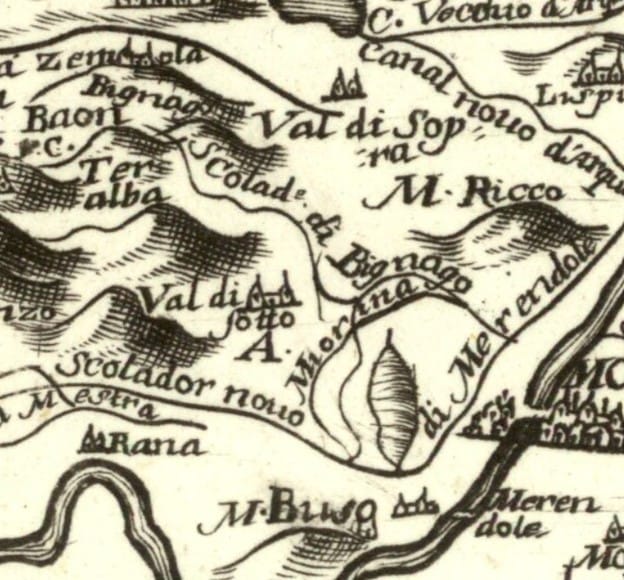

Years ago I lived near the area of the Colli Euganei (the Euganean Hills). They only rise to between 300-600 metres in height, but with everything else around them being completely flat, they do stand out. The area is named after an ancient pre-Roman tribe that inhabited the area, although little is known about them.

The Colli Eugenei have several legends, almost all involving women. Like many folktales and legends, most are rooted in historical fact. Here I recount three such tales and provide them with some historic context.

Let's explore the first story:

Donna Daria and the Fireflies

The legend speaks of Donna Daria, a lady (a countess), living in the Lower Valley of San Giorgio in Baone — a tiny village in the Colli Euganei.

One lovely hot summer day, Daria was walking through the forest when she heard the sound of hoof-beats coming towards her. Never knowing what danger might come from unknown riders, she hid herself among the trees and saw the much-feared Ezzelino da Romano. Ezzelino was on his way to Padova along with his army. With him were carts filled with prisoners of war, both dead and alive.

Among the dead she spied the face of her beloved nephew, Guglielmo. He had been decapitated. Deeply saddened, she was nonetheless determined to follow this fearsome army into the depths of the valley where she hoped to find the body of her nephew after Ezzelino disposed of his prisoners.

Despite fear and knowing that it would be dangerous to touch Ezzelino’s victims, and even though it was growing dark she clambered over and under the brush of the valley. Given the descending darkness, she feared that it would be impossible to find his head.

Daria prayed to the Blessed Virgin for help and there, in the midst of almost total darkness came hundreds of fireflies to guide her to Guglielmo’s head. Once she found his remains and by the fireflies’ light, she wove a travois of branches. The fireflies then led her and her burden to a local wise woman. The two women attached the travois to an ox, and taking only the most hidden pathways eventually reached the Chieso del Santo at Padova, which at the time was very small chapel. There they buried Guglielmo’s head.

Much later Daria died and was buried in the San Giorgio Valle cemetery. It is said that on a certain night in July, hundreds of fireflies gather at her grave and then fly to retrace her steps to find Guglielmo, and then to the Church where his head is buried.

Before we delve into the other stories, let’s examine the historic Lady Daria,

Daria da Baone di Camposampiero

Daria was indeed a Lady of rank and a member of the Baone family, a daughter of Alberto da Baone, and she was the second wife of Gherardo da Camposampiero (1150-1222). Gherardo already had a son from his first wife, Ortensia (whom he later repudiated), named Florio. With Daria, he had three children: Tisolino (who died young in a military conflict in 1222), Maria (who may never have married), and India who went on to marry “well”.

There is more documentation on the headless Guglielmo (or Guglielmino) da Camposampiero.

Guglielmino da Camposampiero

Guglielmo was born in Padova in 1225, the son of Giacomo di Tiso IV and Maria da Vo.

He wasn’t with his parents for long. His father died in 1228, when little Guglielmo was only three, and at that the same time he was taken prisoner by Ezzolino III da Romano. Eventually he was rescued by his grandfather Tiso, who gathered a small army against “Ezzolino the Tyrant”.

Guglielmo was only eight years old when, in 1234, his grandfather died, making the young boy the head of a prominent family in the Padova area, which was ruled by Ezzolino. Once again, Guglielmo was taken prisoner (or hostage). He later reported that he was well treated and was eventually released through the negotiations of the Vo (his mother’s family).

Things seem to settle down until Guglielmo, for whatever reason, married a woman named Mabilia Dalesmanni. Her family and clan was hostile to Ezzolino. He was again thrown into prison, this time in the tower at Angarano (near present day Bassano del Grappa). There was to be no redemption this time.

Despite Ezzolino’s wishes, Guglielmo refused to divorce Mabilia and for this he was condemned to death. On July 24, 1250 at the age of 25, he was taken back to Padova, brought to the public square, dismembered, beheaded and his body parts were to left “to be eaten by dogs” with orders that no one (other than stray dogs) was to touch the remains.

Daria would have been both brave and frightened when she went into the plaza to collect the sad remains of her nephew. There is documented evidence that she, her daughter Maria and some of their servants (who must have been equally if not more terrified to obey their mistress and spite such a powerful man) defied Ezzolino’s orders, bringing what was left of Guglielmo to the Church at St. Antonio in Padova for a proper burial.

There is further documentation that Guglielmo left some of his money to his daughter born of Mabilia, and other assets to some knights, but it is unclear if his wishes were adhered to.

Now let’s talk about the man Daria understandably feared:

Ezzolino III Da Romano

On April 25, 1194 Ezzolino was born into a German family that had originally come to Italy with Emperor Conrad II in 1036. This family founder, Eccelin, was given a fief called Romano in the area around Padova (“Da Romano” has nothing to do with Rome). His mother, Adelaide Degli Alberti di Mangona, came from a family of counts in Tuscany.

Adelaide: Witch, Devil's Mate — Beautiful or Homely?

Adelaide has a few footnotes in history. The Mangona family was renowned for its beautiful women, but it seems Adelaide was perhaps slighted in this regard. A chronicler of the time waxes on and on about her sister, Beatrice:

“and from Mangona comes Beatrice the beautiful, and Donna Adelasia her sister.”

Yet other sources claim she was a beauty — a femme fatale — and mention that she was "chatty" (a trait rarely ascribed to noble women at the time who were seen, not heard, and merely marital pawns in dynastic games). It was also said that her family was peopled with "rabid" individuals. Chroniclers talk of her walking along the parapets of her castle's walls, dressed in black in the dead of night, carrying "strange objects". She would stare at the sky with her "large black eyes", ravens and crows encircling her while the wind would dishevel her long black hair. Quite the picture was painted of a woman who the chroniclers gave many names: Adeleita, Adelaide, Adelasia, Adelheid, Aldreca, and even Adalegita.

What does seem factual is that Adelaide was, unusually for a woman, a talented astrologer.

According to Rolandino's chronicle, she:

“…possedeva perfettamente la scienza dell’Astrologia e conosceva le vie delle stelle cogli altri moti celesti…”

Meaning:

"She perfectly possessed the science of Astrology and knew the path of the stars and other heavenly bodies"

In any case the main rumour pertaining to Adelaide was that she was a witch, and that she had mated with the Devil himself to sire Ezzolino. It was said that when he was born, she was never able to smile again.

Adelaide died at around 50 years of age (about 1220) and is supposedly buried among the ruins of the Rocca di Cerbaia in Prato (central Italy) where she first met Ezzolino's father (or the Devil, depending on who you believe).

Ezzolino's Youth and Manhood

Ezzolino was the eldest son in the family and was known to be a violent and belligerent youth.

Nothing definitive is known about his childhood other than at the age of four he was sent as a hostage to Verona. There isn’t any mention of him again until 1213, when he participated in the siege of the Este Castle (the Este’s were enemies of his father). A chronicler of the period (Rolandino of Padova) remarked that young Ezzolino showed a keen interest in siegecraft and had a fiery hatred for the Este family — both traits would be characteristic of him throughout his life.

In 1233, his father split up the family’s massive holdings between Ezzolino and his younger brother Alberico. Then, just two years later, his father died and Ezzolino came into his own. He was a mature man of about 39 years of age when he truly found his footing as a cruel despot and powerful tyrant.

Chroniclers of the time described him as "small", "contemptuous", and with an "evil stare" — likening him to the Antichrist.

Despite, or perhaps because of this nefarious person, Emperor Frederick II aligned himself with Ezzolino. The latter quickly began laying siege to various towns and cities, fighting, burning, pillaging, raping and conducting violent military campaigns — too many and too complex to outline here.

The First Wife is a Quick Act I

In terms of his relationships, in 1221 he first married a noble Veronese girl named Zilia, but shortly after repudiated her.

The Second Wife is a Wild Woman

In 1238 he married the Emperor’s daughter, Selvaggia. Selvaggia is an interesting, if obscure, individual. Her name (which I love) means “savage woman” or “wild woman”, but there is no reliable documentation to explain this choice. She was the daughter of an unnamed concubine of the Emperor (he had several).

Selvaggia is also known as Selvaggia of Staufen. She was born in 1225 and on May 23, 1238, in the Church of San Zeno in Verona, was married to Ezzolino. Six days were spent in celebration of the marriage of a 13-year-old girl to a man 30 years her senior. Although this age disparity was not remarkable at the time among noble families, one wonders what little Selvaggia thought of her fearsome new spouse.

Whatever she thought, she didn’t ponder it for long. Some say she was a beautiful girl, and so triggered the jealousy of Ezzolino. By 1244, six years into the marriage she was dead, by order of her husband, according to some. She was buried in a hurry, and where she was laid to rest is unknown. Nothing remains of her — no pictures, no signatures, nothing — except, possibly, a piece of fabric with embroidered designs on parrots on it, now part of a museum collection of ancient textiles.

Marriages Three and Four

That same year, in 1244, Ezzolino marries and divorces another young woman: Isotta Lancia. She dies ten years later in 1254.

His final marriage in 1249 was to Beatrice Maltraversi (or Buontraverso, depending on which source is preferred). This is a year before Daria collects Guglielmo's body parts.

None of Ezzolino's legitimate spouses gave him any children, but he did have one illegitimate son, named Pietro (some believe he was Beatrice’s son born prior to their marriage). Evidently he had some issues with Pietro, as he had him imprisoned in Angarano Castle in 1246.

Sometimes called the tyrant, Ezzolino had a truly dreadful reputation due to his many reported cruelties (once again, too numerous to outline here), and that reputation gained his inclusion in Dante’s Inferno. The poet places Ezzolino in the 7th Circle, 1st Ring, where those who do violence against their neighbours are tortured for eternity. Ezzolino was placed in a river of blood that reached his eyebrows.

Ezzolino and the Da Romano Family Comes to an End

Emperor Frederick died in 1250 (a busy year for our protagonist), and Ezzelino quickly aligned himself with Conrad IV (the son of the German Frederick). Despite this new alliance, Ezzolino's cruelties had provoked widespread disgust — so much so that he was excommunicated by Pope Alexander in 1256.

On September 27, 1259, Ezzolino attempted to capture Milan, meeting rival forces at Cassano. Wounded there and taken prisoner, he became enraged, tore the bandages from his wounds, and refused to eat or drink. He died at Soncino on October 7, 1259. The following year his brother Albert was put to death, and the Romano family became extinct.

─── ❖ ── ✦ ── ❖ ───

The Mermaid of Lispida Lake

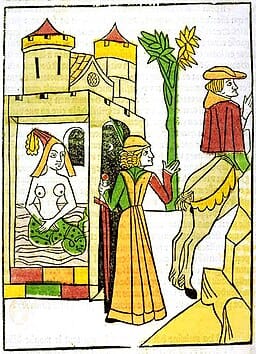

The young Count Manfredo di Monticelli, who was perhaps around 25 years of age, was suffering from a serious arthritic condition involving his limbs. On the night of St. John, he went down to the Lake and cried out “everyone is happy, but not I”. He was considering throwing himself into the lake but then a beautiful young woman emerged from the waters and asked “How can you be unhappy when all is so beautiful?” Completely captivated by the woman, Manfredo replied that all his joints were frozen. The women said nothing, but when she turned to dive into the lake, Manfredo saw that she had the scaly tail of a fish. The lovely mermaid reappeared with hot black mud from the thermal bottom of the lake. She smeared this mud over all Manfredo’s body and began to sing.

Manfredo was cured. He came to seek out the mermaid each night; both were deeply in love. Not knowing how to maintain the relationship, the mermaid swam to Venice to get advice from a wise woman there, despite knowing that the King of the Animals had forbidden her to leave the lake. He discovered her in Venice and her punishment for having betrayed her own kind was to condemn her to being human. She was actually delighted at becoming human, but there was one problem. She did not have a human soul. Wandering high and low, seeking a soul, she found herself praying in a church, when she heard a voice that said “Go in peace. Your lover will share his soul with you”. And so, the two young lovers, two bodies sharing one soul, lived happily ever after.

Touching and delightful, this story has almost no hard documentation. The Monticelli’s did exist in the area, but there is no Manfredo listed in the family genealogies. The lake existed and still exists today, and still is considered a place of healing.

Like a true fairy tale, as I’ve written in other tales before:

There once was — or there once was not — a story, in the oldest days and ages, in a land so far away it was beyond seven mountains, beyond seven rivers and beyond seven forests. It was a time unlike any since, a time when the aspens grew apples, the willows produced lilies, and the animals would throw themselves toward the skies to bring back stories from the back of beyond.

─── ❖ ── ✦ ── ❖ ───

Berta the Peasant, Berta of Savoy and the Skeins of Thread

The last story I will relate tells of a local peasant woman named Berta, who encountered Berta of Savoy (1051-1087) , the wife of Emperor Henry IV.

The Empress Berta was visiting the Colli where a farmer, also named Berta, begged for clemency for her husband who had been unjustly imprisoned for not having paid tithes. Berta took pity on her namesake, granted the farmer clemency, and in gratitude Berta the Farmer gave the Empress her only possession of value: a skein of thread. The Empress was moved by the gesture and told the farmer’s wife that she could claim any patch of land that the thread from the skein could enclose.

Once the other women in the area learned of Berta’s good fortune, they all raced to the Empress carrying skeins of thread. But the Empress was not impressed and told them “the time when Berta wove is ended”. Now this is an expression in the area to signify an event or time which cannot be repeated.

Berta of Savoy

Berta of Savoy was a real person who lived from 1051 until 1087, and was the wife of Henry IV. Upon her marriage she became the Queen of Germany at the age of 15 in July, 1066. She later reigned as Holy Roman Empress from 1084 until her death in 1087.

Berta had been betrothed to Henry as a four year old — and he was only five. Supposedly she grew into an attractive woman, but Henry despised her. He is reported to have had several concubines after his marriage to Berta, and whenever he spotted a young and attractive wife of another, he requested her services, by force if necessary. In any case, he tried to avoid seeing or having anything to do with Berta.

Things reached a breaking point in 1069 where Henry tried to repudiate her, declaring publicly that he had lied for years about getting along with Berta when he had not. He said he couldn’t live with deception any longer and that, as he found Berta repellent, he would not be able to perform his duty and produce heirs with her. He also added that he had never had relations with her and that she was “as he received her, unstained, with her virginity intact” (One wonders if England’s Henry the VIII remembered and changed a few bits of this history for his own benefit?).

The German Church and aristocracy debated, discussed, and were uncertain about what to do. Berta meanwhile went off to a convent. No one could find a legal reason for Henry to ditch Berta, but it would seem that the German court was hesitating due to fear of Berta’s mother, the powerful and well-connected Adelaide of Savoy.

In any case, Henry decided to “reconcile” with Berta, brought her back from the convent, and one year later in 1070, their first child, Adelheid, was born.

Still troubles followed Henry, who was excommunicated in 1076. In order to resolve the issue, Henry had to go and meet with Pope Gregory — who at the time was at Canossa in Northern Italy. Henry, his son Conrad (born in 1074), and Berta all began the dangerous journey to meet with the Pope, and this is when the encounter in the Colli Euganei may have happened.

By January 1077, Henry and Berta were walking around the frozen area (it had been an exceptionally severe winter that tear) of Canossa, barefoot, making penance for their sins. Their supplication worked, and that freed Henry up to besiege and occupy Rome, allowing him to be declared Holy Roman Emperor, with Berta as his Empress, on March 31, 1084.

She wasn’t Empress for long, dying at age 36 in December 1087. Not one to be alone, Henry married Eupraxia of Kiev (who changed her name to Adelaide) in 1089 but that relationship fell apart in 1093 or 1095.

Eupraxia's Troubles

What led to the parting began when Henry was once again traipsing about Italy making war. He brought Eupraxia with him, but kept her in a prison at San Zeno in Verona. In 1093 she managed an escape and ran to Canossa (remember, where they had walked around barefoot in the snow?) looking for help from the enemies of Henry. She accused Henry of all kinds of things: that he imprisoned her, held her against her will, forced her into participating in orgies, conducted a Black Mass over her naked body, conducted obscene rituals and at one point tried to get his son Conrad (Berta’s son) to have sex with her (he refused).

When Eupraxia became pregnant, she found her escape. Since Henry had forced her to participate in orgies, she had no idea who was the father of her child — and so she could leave him on the grounds of being damaged goods. Interestingly, she never did have a child, so perhaps the pregnancy was simply a convenient fiction.

Eupraxia then decided to go far away, to Hungary. to live in a convent until 1099. When Henry died in 1106, her "earthly husband" was no longer an impediment and she was free to become a nun. She died in July 1109 in Kiev.

Would you like to read other posts? If so, please click the Home Page link below:

You, Dear Reader, are much needed and appreciated.

Everything written requires a reader to make it whole. The writer begins, then you, dear reader, take in the idea and its image, and so become the continuation of its breath. Please subscribe so that my words can breathe. Consider this my hand, reaching out to yours.