Everything Happens for a Reason? I Don't Think So.

There are a few common platitudes that irk me, and “everything happens for a reason” would be in my top five (tied with “whatever doesn’t kill you makes you stronger” — watch for an upcoming essay on that hackneyed phrase).

Many Things Happening for Many Reasons?

First of all, I would like to explain the choice of the image at the top of this page. Painted in about 1530, it is entitled the "Allegory of Fortune" by Dosso Dossi (more properly Giovanni di Niccolò de Lutero). Now here is a fascinating turn of the Wheel of Fate…

The painting had been found at a flea market and bought cheaply by an anonymous individual. This buyer later tied the seven-foot work to the roof rack of his car and took it to Christie's auction house in New York City, where excited experts of the auction house identified the painting as a long-lost scene by Dossi.

Dosso Dossi was known for allegorical work, complex and filled with symbolism. He believed that prosperity was fleeting and mostly due to luck. In this painting the woman represents Lady Luck complete with a cornucopia of good things — yet she sits on a bubble that could burst at any moment. She only wears one shoe — representing either good or poor fortune. The man represents "Chance" and holds a handful of lottery tickets (yes, they did sell lottery tickets way back then, too).

This image somehow seems more than fitting to introduce the topic of everything possibly happening for a reason.

I will get into my reasons for finding this expression silly at best, but first I wanted to see how it came to be. What I discovered was certainly unexpected.

First Appearances

Up until 1940, the exact expression “everything happens for a reason” did not appear in print at all. From 1940 until 1960, it is found only four times. Then, through 1986, it begins to be used more often, but primarily in writing associated with science, sports, children’s stories and mechanics. This would make sense; the usage most often referred to consequences of scientific or mechanical interventions: think along the lines of “if you pull this lever, then this pulley will activate”.

In 1986, the expression appears in printed works — to be precise, in 0.0000000010% of published books, journals, articles, magazines and so on. It increases ten-fold by 2000, and as of the end of 2022, the prevalence has increased to 0.0000003480%.

What an extraordinary ascent: Better than Bitcoin!

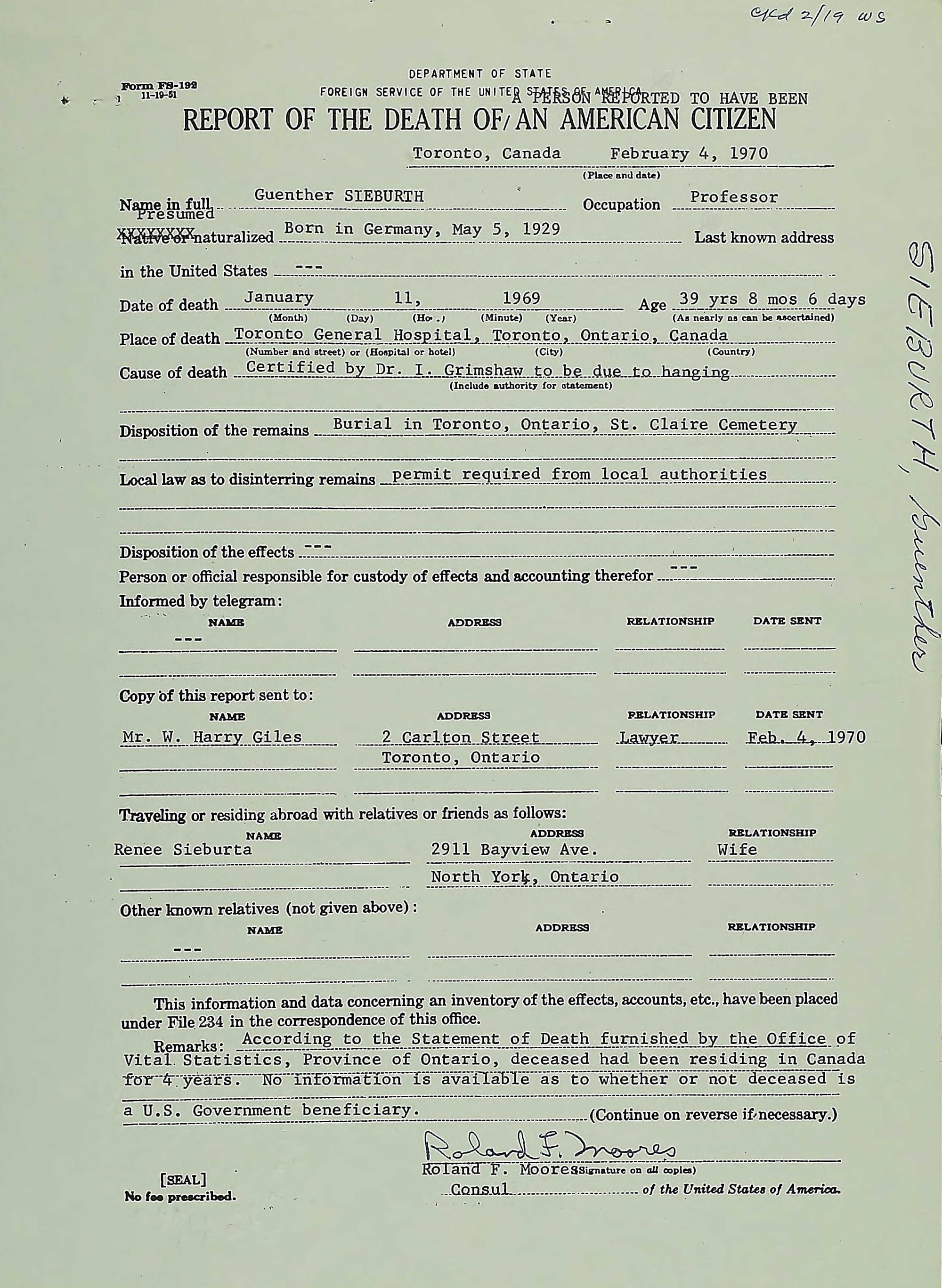

From what I can find, the very first instance where “everything happens for a reason” appeared in the context of philosophy was in a thesis written in 1966 by Guenter Sieburth at the University of Wisconsin. His 800-page opus was entitled “On Ancient Measure, Volume 1” (there do not appear to have been subsequent volumes). In it he states:

Leucippus held that everything happens for a reason and by necessity. This is not to be taken in the same sense in which such a statement might be made by a Philolaus , who saw in the cosmic order the effect of divine rationality.

Leucippus, for those who are curious, was a pre-Socratic Greek philosopher from the 5th century BCE. Almost nothing is known about his life, but his beliefs are well documented. He is considered the founder of “Atomism”, where he believed the world was divided into two parts. The first part consisted of atoms, or indivisible particles, that make up all things. The second part was the “void” which referred to the emptiness between the atoms.

The atoms of our Greek philosopher were in constant motion and constantly colliding, by which he developed a deterministic notion of how the world was created, and how it worked.

The other philosopher mentioned by Sieburth was Philolaus; again a pre-Socratic Greek. Both a mathematician and a mystic, Philolaus is a fascinating thinker, and possibly the first known Western philosopher to put forward that the Sun was the centre of the universe and not the Earth.

Both these Greek philosophers are well worth looking into but are beyond the scope of this essay.

Returning to Guenter, he also wrote another dissertation entitled "The Axioms of Mathematics and Ontology in Aristotle’s Philosophy". Clearly Guenter was a deep thinker and an educated man. Yet, little did he know that his innocently coined phrase would take on such a life of its own in pop-psychology, appearing in memes, on coffee cups and motivational swag. I wonder what he would have thought, especially since the later use of “his” phrase was interpreted in an opposite sense to what he wrote back in 1966.

Who was Guenter Sieburth?

A quote from Bertrand Russell’s “A Free Man’s Worship” is engraved on Sieburth’s tombstone:

Man is yet free during his brief years, to examine, to criticize, to know, and in imagination, to create

We can’t know whether this phrase was particularly meaningful to him or whether his family chose the inscription — but it does seem fitting. I rather like it, too.

Guenter was born in May 5, 1929, in Pila, Poland. From a Jewish family, his name was variously spelled as Guenter or Guenther, and his surname may have been more correctly Cohen-Sieburth. He immigrated to the United States in 1936, along with his parents and sister, Anneliese. She was born two years prior to Guenter, and she died in 1948. She was only 22 years old.

In 1957 he married Renee Therese Schimmel. Born in Cologne in 1934, she arrived in New York from Belgium at the age of 13. She was described as 5’2” tall with chestnut hair and eyes, and weighing a meagre 98 lbs. She was travelling with her mother, Frieda Schimmel, a holocaust survivor (Renee's father was killed in Auschwitz).

Guenter pursued various university degrees, moving around the United States, working as a professor, and eventually settling in Cook County (Chicago) Illinois. In around 1965, Guenter moved to Toronto, Ontario. (I cannot find why he moved to Canada.)

In a family already beset with tragedy, their tribulations were not over. About four years later, in Toronto, January 11, 1969 was a cold and windy Saturday; the temperature only reached a high of 15 degrees Fahrenheit, and there were snow flurries. The sun rose just before 8am and set at 5pm, and sometime between that sunrise and sunset, Guenter died by hanging.

The documentation doesn’t specify whether it was a suicide, although there is no mention of foul play. Everything happens for a reason? I’m not so sure in the case of Guenter and his family.

Pareidolia, Apophenia and Nazi Germany

To my mind, “everything happens for a reason” is philosophical manifestation of pareidolia and apophenia.

Many people are familiar with pareidolia, even if they are unfamiliar with the term itself. Simply put, pareidolia is a psychological tendency to see the familiar where it doesn’t exist. Usually manifesting itself with faces and animals, some examples would be “the man in the moon”, various shapes formed by clouds, and religious imagery — like Jesus’ face in a miraculous muffin from the coffee shop. We often try to organize random imagery into something recognizable.

In the 2002 film “Signs” directed by M. Night Shyamalan, the protagonists witness what may be an alien invasion of the Earth.

One of the main characters, an apostate priest, explains his thinking:

People break down into two groups. When they experience something lucky, group number one sees it as more than luck, more than coincidence. They see it as a sign, evidence, that there is someone up there, watching out for them. Group number two sees it as just pure luck. Just a happy turn of chance.

I’m sure the people in group number two are looking at those fourteen lights in a very suspicious way. For them, the situation is a fifty-fifty. Could be bad, could be good. But deep down, they feel that whatever happens, they’re on their own. And that fills them with fear. Yeah, there are those people. But there’s a whole lot of people in group number one. When they see those fourteen lights, they’re looking at a miracle. And deep down, they feel that whatever’s going to happen, there will be someone there to help them. And that fills them with hope.

See, what you have to ask yourself is ‘what kind of person are you’? Are you the kind that sees signs, that sees miracles? Or do you believe that people just get lucky? Or, look at the question this way: Is it possible that there are no coincidences?

It would seem that those who believe “everything happens for a reason” belong to group number one in the aforementioned speech from “Signs”.

Circling back to apophenia, the term was coined back in 1958 by Klaus Conrad. He meant it to explain the “unmotivated seeing of connections” along with “abnormal meaningfulness”. Under this heading Klaus would list conspiracy theories and superstitions at one end, schizophrenia and paranoia at the other.

A little background on Klaus: Born in Czechia in 1901 (he died in Copenhagen in 1961), he was a German neurologist and psychiatrist. He joined the Nazi Party in 1940 and had a (surprisingly? unsurprisingly?) successful career after the war as a professor of psychiatry and neurology. Until his death, he was also a director of the University Psychiatric Hospital in Göttingen. According to medical literature, he made significant contributions to the understanding of the early stages of schizophrenia.

Why the Idea of “Everything Happens for a Reason” is so Appealing

In addition to apophenia, I think the appeal has something to do with self-comfort and pseudo-religion. People can take a difficult experience and believe that there are perhaps complicated and often inapparent reasons for it; not unlike the Christian belief that we cannot know the mind of God, who “works in mysterious ways”.

Of course, this belief system, like most religions, cannot be proven — not empirically, nor even logically and theoretically. But I imagine it provides a certain level of comfort. In this world, things are not random, events are meant to be, we play a meaningful part in the universe — we just don’t know what it is. Consequently, if one is a person of “faith” who believes in an all-knowing powerful god-entity, then this comforting conviction allows one to fit in nicely with the divine plan.

We, as humans, like stories. We especially like those that have a beginning, a middle and an end; stories that flow and make sense. When some random event occurs, the notion of “everything happens for a reason” further serves the narrative and helps explain the unexpected, the jump in the video.

Here is an example of, in our current zeitgeist, how baked-in this notion of deeper meaning is. Take the unflagging popularity of books endorsed by Oprah Winfrey in her Oprah’s Book Club picks. Most (but to be fair, not all), follow a formula. It almost seems that the authors she endorses attentively read Stephen King’s “On Writing: A Memoir of the Craft”, where he outlines “The Three R’s — Rebellion, Ruin and Redemption”. Following King's recommendations, the protagonists at the start are often rebellious and feisty, but misguided. They stage some sort of rebellion against whatever is bothering them, and usually the consequences are ruinous. Finally, the character finds atonement, forgiveness, and — importantly — meaning. Even Stephen King believes that "everything happens for a reason" is a winning formula — at least in fiction.

Leaving the literary world and returning to the quotidian and conversational, what I find particularly irksome is when someone tries to comfort another using this trite phrase. It’s facile and pat at best, and seems to convey that the person speaking the platitude has nothing to say, nothing to add, and reaching into their cupboard of empathy, has found it empty.

Me? Well, I’m a member of group number two from the “Signs” soliloquy: I find more comfort in looking at a random event, a change, or an unexpected happening, and using it to learn, grow, inquire, and perhaps develop resilience.

To paraphrase Descartes: Shit happens, therefore I am.

And perhaps this final viewpoint is more in line with Guenter’s tombstone engraving.

Would you like to read other posts? If so, please click the Home Page link below:

You, Dear Reader, are much needed and appreciated.

Everything written requires a reader to make it whole. The writer begins, then you, dear reader, take in the idea and its image, and so become the continuation of its breath. Please subscribe so that my words can breathe. Consider this my hand, reaching out to yours.