Brain Fever - The Difference Between Compassion and Empathy

Several years ago I watched a wonderful film called “Awakenings” which was based on the autobiographical book of the same title by Dr. Oliver Sacks.

When I originally chose to watch the movie, I had little idea of the subject-matter. The story follows Dr Sacks (played by Robin Williams) working in a facility that housed many patients in a catatonic state. He discovered what each patient had in common with the other: all had contracted encephalitis decades earlier. The patient who was the central focus of the movie was Leonard Lowe (played by Robert DeNiro), a forty-one-year-old who had been in his current state since he was eleven years old. That state was likened to being “frozen” and he had been that way for 30 years.

When I watched the actors portraying the mostly catatonic patients and learned the cause of their malady, I found myself almost in shock. I understood completely what the patients were experiencing because many years prior I, too, had been infected with the virus causing “brain fever”.

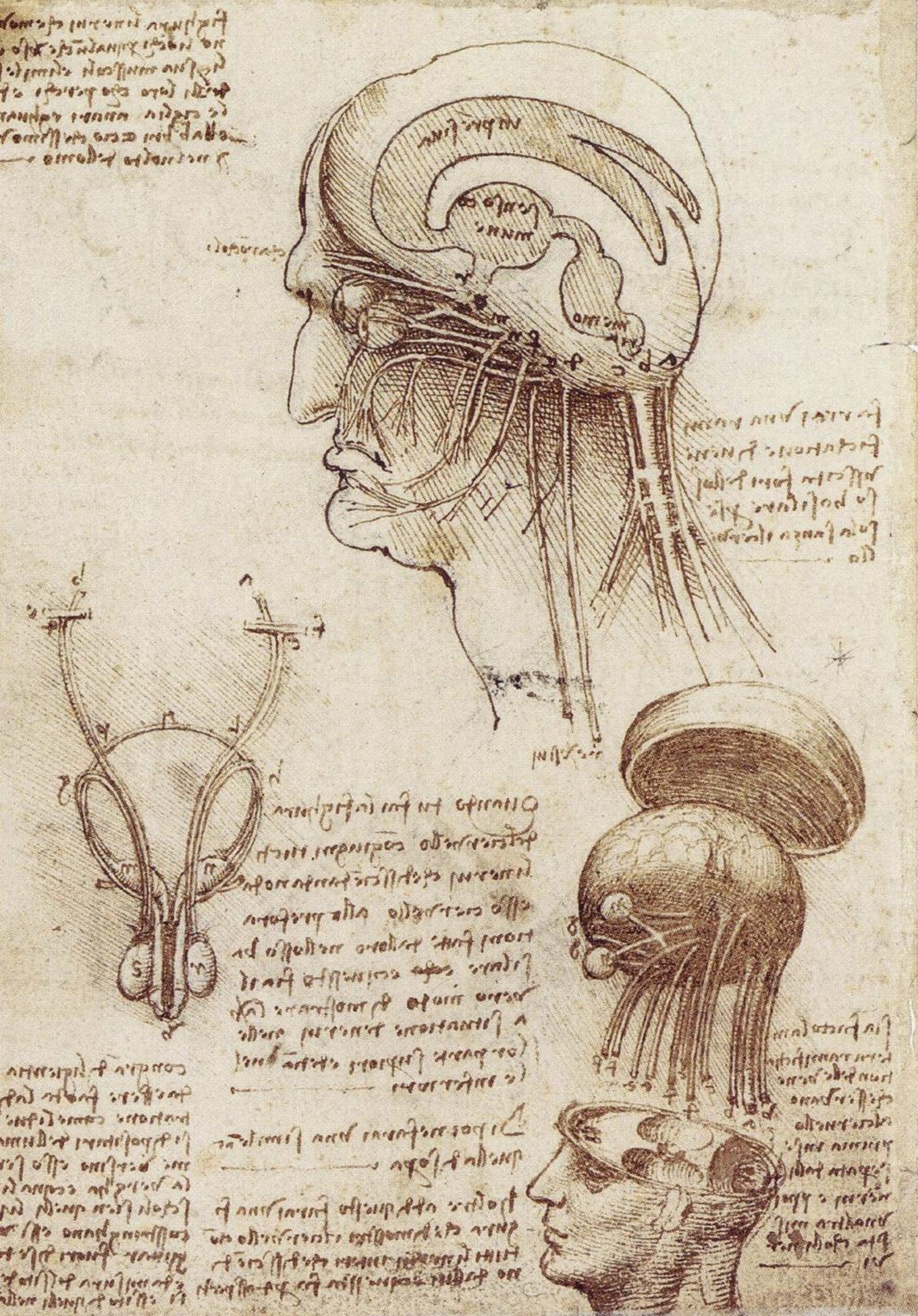

There are many websites that describe the multiple and varied forms of encephalitis, but the variety that best describes what I experienced is called “lethargica”. According to the medical literature, this particular form of the disease “attacks the brain, leaving some victims in a statue-like condition, speechless and motionless”.

One morning when I was a young child (I don’t remember exactly what age), I awakened to find myself paralyzed. I was unable to move my body or to speak, but I could still see and hear. My mother had entered my bedroom at the regular time in her usual way, that is by saying in a relatively loud voice “time to get up”, fully expecting me to get up and pad over to breakfast.

When I didn’t come to the kitchen, she returned to my room rather angrily. She told me to get up in a much firmer voice and, when I didn’t respond, she grabbed my wrist to give me a shake. That was the moment she panicked. I was completely rigid and hot from fever. Despite the paralysis I could move my eyes and see, and I still remember the fear in her face.

She called our doctor’s office and when explaining the situation was told that the doctor was coming over right away. This was in the 1960s and, even then, house calls were a rarity. The fact that a doctor wanted to come immediately ratcheted up her anxiety to a new level.

Meanwhile, I was completely aware of my surroundings, but totally unable to move. I don’t recall feeling fevered or uncomfortable in any particular way. I was merely perplexed by what was happening and rather afraid of getting in trouble for being disobedient.

At some point the doctor confirmed that I had contracted encephalitis (I don’t remember what tests were done to determine this) and the Provincial Health Office had been advised. I later learned that my case was isolated, for which the medical officers were relieved, as they feared that this might have been the start of a dangerous epidemic.

I did have a raging fever and was completely paralyzed for some time, but no pain; just the odd and vaguely frustrating sense of awareness and being unable to interact.

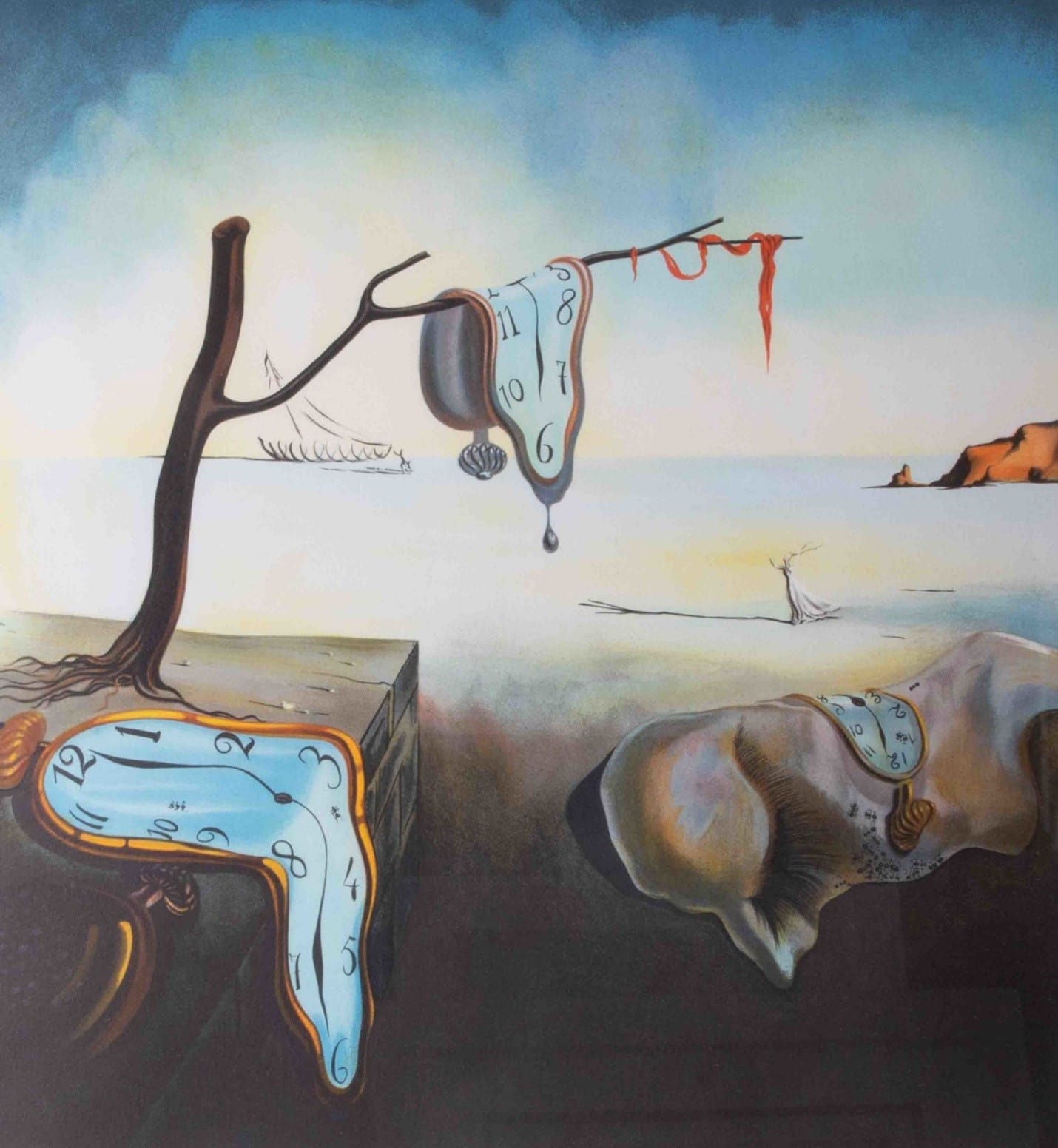

The doctor prescribed some pharmaceuticals, and within about 12 hours of taking them, my fever lessened, and my limbs began to unlock. The feeling was unforgettable as the drugs began to work. I felt as though my legs and arms were stretching and turning into liquid and melting off the bed as though I'd been transported to some bizarre Dali-esque world.

In any case, I recovered, and that would have been the end of the story — until I watched “Awakenings”.

I cannot express how I was struck by seeing the paralyzed and catatonic patients. I knew exactly how they felt and could empathize deeply with them. But I had no true understanding of what it must have been like for them to have been aware of their surroundings for decades, with no one realizing it.

To further unravel a thread, the experience of watching the movie highlighted for me the difference between empathy and compassion.

The formal definition of “empathy” is “the action of understanding, being aware of, being sensitive to, and vicariously experiencing the feelings, thoughts, and experience of another”. Note the “and” in the definition; it’s not enough just to understand, to be aware, to be sensitive, or vicariously experience a situation — you must experience all of these effects in order to truly empathize.

On the other hand, “compassion” is “sympathetic consciousness others' distress together with a desire to alleviate it”. That is, compassion, by definition, requires sympathetic awareness coupled with wanting to make things better.

The two are not the same at all.

At present, it would seem that when not lumping compassion and empathy together as interchangeable, we (society) tend to focus on the latter as a solution to the various ills of the world, be they physical, emotional, spiritual, political or societal. But empathy, by definition, doesn’t fix anything.

In contrast, we should be looking more intently at compassion. Compassion is geared to alleviation and solutions. It doesn’t necessarily even require empathy.

Furthermore, I might go as far as saying that empathy is more of an unexacting and facile emotion (at least, in terms of its effect upon others). While perhaps psychologically profound, empathy does not require a desire for positive change, let alone an internalized call to action — whereas compassion entails concern for, and a motivation to improve, the welfare of another individual or group. Yet, empathy can fuel and fan the flames of passion in compassion.

I believe that the notion of “Dunbar’s Number” further complicates our ability to be compassionate. Dunbar’s Number is a theory that posits there is a cognitive limit of 150 individuals in human groups.

Dunbar’s Number was first put forward in the 1990s by a British anthropologist named Robin Dunbar. Like most theories, it has been the subject of debate, conjecture, and criticism, primarily disputing the number of 150 individuals. Regardless of the number, in the context of empathy and compassion, I don’t think the exact figure is consequential; rather it is the matter of what a limited sized cognitive group means. And, boiled down to the ability to empathize or to feel compassion for others, the effective number is relatively small indeed.

Add to this another complication best defined as the “Identifiable Victim Effect”. This theory[1] asserts that people are more inclined to help a specific and identifiable person (the “victim”) as opposed to a large and less defined group, even when both have the same needs.

Put together these two theories, and you’ll find a moderately clear path to selective empathy, but a murky road to compassion.

“A single death is a tragedy; A million deaths is a statistic.”

— Often attributed to Stalin, the source of the quote is unknown

This quote further illustrates the easier path to empathy (the single death) and the harder road to compassion (the million deaths).

Perhaps our general inability as a society to truly effect positive change is due to a combination of Dunbar’s Number, the Identifiable Victim Effect and our penchant for what is easy; empathy being a simpler path that seems noble and good but does nothing to ameliorate anything.

In any case, viewing this film was the most profound and true experience of empathy I’ve ever had.

[1] Jenni, Karen; Loewenstein, George (1997-05-01). "Explaining the Identifiable Victim Effect" (PDF). Journal of Risk and Uncertainty. 14 (3): 235–257. doi:10.1023/A:1007740225484. ISSN 0895-5646. S2CID 8498645.

Would you like to read other posts? If so, please click the Home Page link below:

You, Dear Reader, are much needed and appreciated.

Everything written requires a reader to make it whole. The writer begins, then you, dear reader, take in the idea and its image, and so become the continuation of its breath. Please subscribe so that my words can breathe. Consider this my hand, reaching out to yours.