Being A Human Book

Really, it’s true — literally (pardon the pun).

I recently participated as a Human Book in an event of the Human Library Organization.

What is the Human Library Organization?

The Human Library Organization was founded in Denmark 25 years ago and operates in 85 countries. Their tagline is “unjudge someone”. Their primary focus is to give people an opportunity to learn about the life experiences of a person with whom they might not have an opportunity to interact under ordinary circumstances. They provide a safe, anonymous space, and a unique approach. All sorts of different people, topics, lifestyles, and experiences are presented. There are books about unusual occupations, immigration, marginalization, adoption, 2SLGBTQ+, transgender, war, refugees, non-mainstream religious practices, various disabilities, and abuse to name a few. Some books, like mine, represent a common journey that many of us either take or that we travel with others. We’ll get into my book shortly.

What Exactly is a Human Book?

A Human Book is just what is says it is. Like in a regular library, there are sections or headings, such a social studies, health, gender studies, and so on. Each Human Book presents an episode, or chapter, from their life as a topic under a heading, such as those listed above, with a short title. Some examples might be: “Autistic”, “Survivor of Child Abuse”, “Refugee”, or “Gay Politician”.

The Human Book presents their story, being very careful not to be preachy or to evangelize their beliefs, but rather factually present their lived experiences. And just like when you are reading a book, a reader can pause, seek more detail or clarity, interrupt, and ask questions.

In this manner, let’s imagine a stereotypical über-masculine longshoreman who could potentially sit down with an urban transgender performance artist — an encounter that neither would likely have in their regular lives. The space is safe, contained, and anonymous.

Each reader “borrows” the book for 25 minutes and at the close of that time “returns” the book to the organizers, leaving feedback on their experience.

My Training: Reading a Human Book

During my training to qualify as a Human Book, I was paired with a young East Indian woman living in Europe. Her book title was “Infertility”. Initially I was not terrifically interested in the topic; I have not personally had issues with fertility and don’t have any close contacts who have. You could say that “I didn’t see the problem”, and how true that turned out to be!

Her story, in brief, was that she had been married for several years, and was living with extended family in a close-knit Indian community in their adopted European country. She explained that culturally there was a strong expectation that she should have children — quickly and several. She did not get pregnant, despite trying. Consequently, over the years, she underwent many painful and invasive procedures in order to address her infertility. After years of unsuccessful interventions, her husband was finally persuaded to have himself assessed.

He is infertile, not her.

Not terribly surprising, but what is deeply unsettling is that she cannot openly acknowledge that the issue resides with him. Not only can there be no acknowledgement of the true source of the infertility; she must continue to go through a painful charade of infertility treatments, using her body to cover the “shame” of her husband.

In my world this is unimaginable. I could be sitting on a bus next to this woman and have absolutely no clue of the mental, emotional, spiritual and physical pain she is subjected to.

I had no idea.

Initially, when learning of the book title, frankly and honestly, I was somewhat dismissive. I didn’t have the first clue of what could be happening, but what is more significant is that I didn’t even realize, ponder or conceptualize that there might be a significant issue behind it. I was — in the true dictionary sense — ignorant. Not willfully so, merely uninformed and deeply unaware of my ignorance.

This, I believe, is an experience that speaks to the heart of the Human Library.

My Book

To be honest, my subject-matter was relatively tame, but one that touches many people as a common or shared experience.

Anyone who knows me will agree that I can be talkative in the extreme. I can be judgy, preachy, overly detailed, easily derailed into side topics, opinionated. A friend once described me as “deceptively open” In other words, I am very open-minded, and consequently I give the impression of being open to discussing my thoughts and feelings. In reality, though, it’s something of a clever façade where I give the impression of doing “open”; in reality I often skirt around core issues. I think she made an astute observation. Ouch!

Despite my friend’s observations, like most people I will usually be happy to share my stories, to pontificate, to proselytize, and have lively conversations. However, I rarely discuss my “heavier” stories. In the case of the Human Library Project, “edgier” topics are sought after.

In keeping with my oddly segmented reticence, I will not get into my Human Book story here (I also need to be mindful of the confidentiality clauses I signed in my agreement with the Human Library).

But in this context, my book title is not particularly relevant. What I do want to convey is what I found initially to be surprising and then, thinking about it, less so.

I was expecting people to want to hear the story, interact, ask questions; what many did was exactly that… but generously peppered with their own experiences, their own fears, their worries. I heard their stories while relating mine.

Not only was there no judgment (in keeping with the “unjudge someone” philosophy of the Human Library); there was a sense of a shared experience and a completely safe place in which to discuss the topic. The closest thing of a similar nature that I experienced was decades ago when I spent a great deal of time riding trains in Italy. There would be an odd situational intimacy and anonymity created by the physical nature of the long-distance European trains of the time. There were closed compartments that sat four people, and you would be with these strangers for up to eight hours – after initial pleasantries one would often hear the most fascinating and sometimes harrowing stories. Then we would descend the train at destination, each moving into our separate lives, no names exchanged, never to see one another again — left only with memories.

Perhaps those people, my “readers”, at the Human Library needed to hear my story and explain how theirs related to mine. I think this is good.

After participating for roughly six continuous hours — never have I had a conversation of that length before — I was physically and mentally exhausted. I went to bed early and dreamed and dreamed.

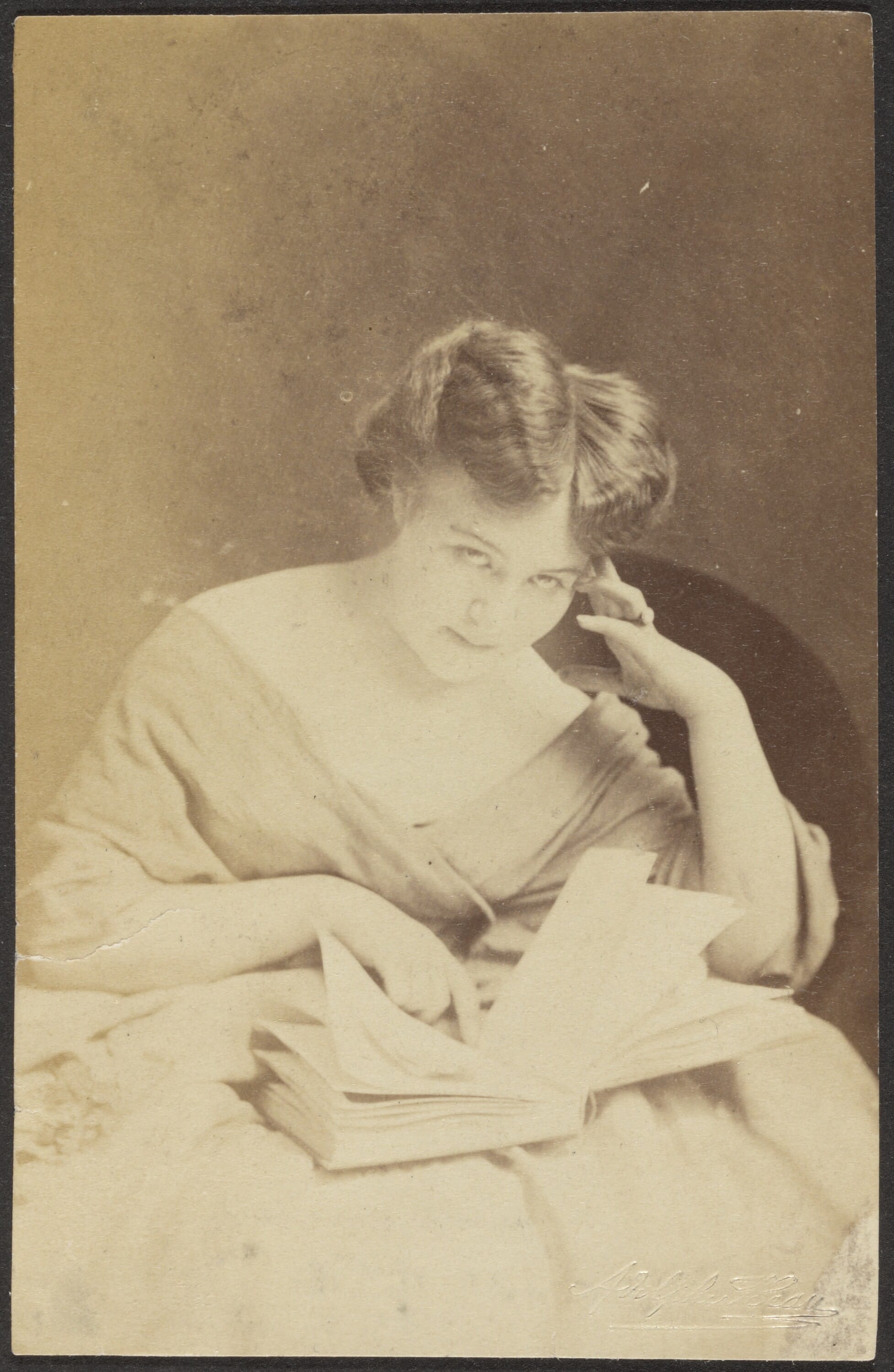

Normally telling people about your dreams is beyond tedious but in this case I feel there is some relevance. I dreamt I was in a large nondescript room where all the furniture had been removed. On the walls appeared outlines of where portraits had been hung. Upon closer inspection, the ghostly images of the people who had been captured in those photographs could be discerned.

Difficult to describe, the images appeared like bluish scorches left upon a wall. Somehow those images seemed to me as though they were the people who came to “read” my “human book” and of those readers' friends and family that they wanted to benefit from our interaction.

I can’t remember when I felt more honoured and helpful.

Would you like to read other posts? If so, please click the Home Page link below:

You, Dear Reader, are much needed and appreciated.

Everything written requires a reader to make it whole. The writer begins, then you, dear reader, take in the idea and its image, and so become the continuation of its breath. Please subscribe so that my words can breathe. Consider this my hand, reaching out to yours.