What the Dictionary Got Wrong: An Etymology of Skedaddle

The Oxford English Dictionary: Distinguished, revered, venerated, respected, hallowed, culturally enshrined. Who could even think of suggesting that this monument, this monolith is not perfect?

The mere notion could be considered iconoclastic at best, or heretical at worst.

And yet, here we are.

I did not set out to be a maverick enfant terrible, seeking satisfaction in finding fault with the Oxford English Dictionary. Being a word-nerd and lover of etymologies, I cherish my exceedingly large hardcover set (to clarify, I own the “shorter” version — two heavy and cumbersome volumes, about the size of a microwave oven, sporting very tiny print). In my bookshop, prior to the ubiquity of Google, this set was referred to as “Big Blue” and was used frequently whenever a word definition was needed (or disputed).

This particular word quest began with my noticing a little commercial van driving by. It was some pest or animal control company with the word “skedaddle” in its name, something I found clever and delightful. Then my mind began its typical trip down strange little byways… Where did the word come from?

Let's start with the definition:

verb: skedaddle; 3rd person present: skedaddles; past tense: skedaddled; past participle: skedaddled; gerund or present participle: skedaddling

depart quickly or hurriedly; run away.

“when he saw us, he skedaddled”

To learn the origins of skedaddle my first stop was the OED, that confidently and rather tersely declared:

The earliest known use of the verb skedaddle is in the 1860s.

OED's earliest evidence for skedaddle is from 1861, in New York Tribune

Feeling somewhat disappointed in the brevity of the entry, I tried the noun form:

The earliest known use of the noun skedaddling is in the 1860s.

OED's earliest evidence for skedaddling is from 1863, in the writing of Charles Hamilton Smith, soldier and natural historian.

The OED is usually far more verbose in its entries. Feeling as though an old friend had somehow brushed me off, I went to see whether Collins, Webster’s, or other some less revered authorities had anything else to say.

All said essentially the same thing, although there was some indication that the word was of “unknown” and “American” origin, likely an unknown American coinage. Collins pegged the first appearance of skedaddle at 1859. Hmm. Intriguing.

Other dictionaries and etymologists cite a variety of sources for the word — Irish and Scots dialects, some local British usages, the odd Scandinavian cognate, and even a few references to ancient Greek. Curiously, the OED does not mention any of this.

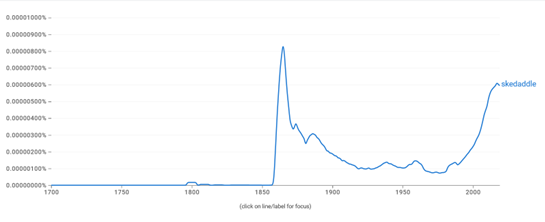

My next stop was the somewhat unreliable but always interesting Google Ngram viewer. For those who don't know about this little treasure, it allows one to search for a word and graph its use over time. It scours the content of websites and printed references (notably digitized Google books) and plots the life of any given word or expression. Unless a word has completely disappeared, almost everything shows an upward trend (naturally, since more and more materials are being published in a variety of formats). Yet what I find more compelling are the usage peaks and valleys prior to the Internet age.

As NGrams go, this is remarkably different than most. There is the usual steady uptick from the 1990s onwards; but look at that dizzying peak starting around 1864. That would coincide with the information provided by the OED.

But what about that tiny rise in usage from 1797 to 1803? Where might that be coming from?

So what might the OED tend not to consider?

I began thinking about “popular” texts, folk tunes, plays, minstrel works, and non-standard English (or Irish or Scots) dialectal usages. And lo and behold, skedaddle appeared!

Going back to 1830 in Dublin, Nugent and Co. published a collection of Irish folk tunes entitled “The Harp & Shamrock Songster, Etc.” Skedaddle appears in the lyrics of the song “Johny [sic] I Hardly Knew Ye”. Some sources cite a later publication date in England, but the Irish collection predates it, as do the original lyrics and unusual spelling.

Earlier still, there is a collection dated 1800 called “Irish Ministrelsy”; once again using the word skedaddle in a song lyric.

More examples can be found in plays, songs but perhaps more tellingly in this collection published somewhere between 1830 and 1840: “Jim Crow's vagaries, or, Black flights of fancy: containing a choice collection of Nigger melodies: To which is added, The erratic life of Jim Crow” (Please forgive the use of the pejorative term; I am quoting a title, not endorsing the word).

And lastly, returning to more “standard” publications, skedaddle is used in The Economist, Volume 403, Issue 8779 from 1843.

Am I nitpicking? Yes, probably, but there are several points to be made:

- not every source is necessarily correct or complete;

- not even the venerated OED is without errors;

- and, more importantly, enshrined authorities tend to ignore certain cultures, marginalized groups or records that don't fit a particular narrative.

But, ’nuf said — it's time to skedaddle!

Would you like to read other posts? If so, please click the Home Page link below:

You, Dear Reader, are much needed and appreciated.

Everything written requires a reader to make it whole. The writer begins, then you, dear reader, take in the idea and its image, and so become the continuation of its breath. Please subscribe so that my words can breathe. Consider this my hand, reaching out to yours.